Calligraphy and the Traditional Chinese Cultural Mindset

![]() We have talked about the features, evolution and major functions of Chinese calligraphy. Now we will talk about the relations between calligraphy and the traditional cultural mindset of the Chinese people.

We have talked about the features, evolution and major functions of Chinese calligraphy. Now we will talk about the relations between calligraphy and the traditional cultural mindset of the Chinese people.

The cultural mindset of the Chinese people can be seen in the painting on prehistoric pottery and the human mask design on a bronze three-legged tripod of the Shang Dynasty displayed in the Museum of Chinese History, in the three halls of the Palace Museum in Beijing and in the Longmen Grottoes in Henan Province. Also, it can be found on tomb bricks of the Qin Dynasty, roof tiles of the Han Dynasty, poems of the Tang Dynasty and rhymed verses of the Song Dynasty.

Calligraphy is an elegant art, with a history of several thousand years, and fully displays the cultural mindset of the Chinese people. Such a cultural mindset is rooted in classical philosophical thinking. It can be dated back to the pre-Qin period and also embraces Confucian and Taoist thought. Confucian thought and Taoist thought supplemented each other, and became important factors promoting and affecting the evolution and development of the aesthetics of calligraphy.

Confucius (551-479 B.C.) was the founder of the Confucian school of thought which was predominant in China for more than 2,000 years, and represented the main social and cultural trends of ancient China. The Confucian school advocated kindness, loyalty, forgiveness and the moderation. Concerning the ideal outlook on life, it advocates progress and optimism. In the field of art, it affirms natural beauty, and emphasizes the integration of beauty and kindness. It believes the art can mold a person’s temperament and educate a person in aesthetics, thus helping that person enter a lofty spiritual realm and promoting the harmonious development of society.

Confucius (551-479 B.C.) was the founder of the Confucian school of thought which was predominant in China for more than 2,000 years, and represented the main social and cultural trends of ancient China. The Confucian school advocated kindness, loyalty, forgiveness and the moderation. Concerning the ideal outlook on life, it advocates progress and optimism. In the field of art, it affirms natural beauty, and emphasizes the integration of beauty and kindness. It believes the art can mold a person’s temperament and educate a person in aesthetics, thus helping that person enter a lofty spiritual realm and promoting the harmonious development of society.

The founder of Taoism, Lao Zi, lived in the same historical period as Confucius, although slightly before him. The essence of the Taoist thought  emphasizes that thinking and behavior should obey natural laws. In its outlook on life, Taoism focuses on retreat, avoidance and passivity. In the sphere of art, it emphasizes the ideal of going back to nature and looking for the quality of nature and human beings. Taoism yearns for artistic romanticism, and maintains that aesthetics should be separate from concrete practice, and that people should not seek after beauty which is combined with benefits and satisfies physiological needs. Real beauty should be natural, and exist in a spiritual realm free from outside shackles. Such artistic aesthetics are more profound than those of Confucianism, and exerted a significant influence on later generations.

emphasizes that thinking and behavior should obey natural laws. In its outlook on life, Taoism focuses on retreat, avoidance and passivity. In the sphere of art, it emphasizes the ideal of going back to nature and looking for the quality of nature and human beings. Taoism yearns for artistic romanticism, and maintains that aesthetics should be separate from concrete practice, and that people should not seek after beauty which is combined with benefits and satisfies physiological needs. Real beauty should be natural, and exist in a spiritual realm free from outside shackles. Such artistic aesthetics are more profound than those of Confucianism, and exerted a significant influence on later generations.

In general, the common aesthetic outlook held by these two schools and displayed in calligraphy and other arts can be seen in the following three aspects: the beauty of simplicity, the beauty of momentum and rhythm and the beauty of moderation.

The beauty of simplicity. Confucianism and Taoism have a common viewpoint in that they believe that nature and all the things in the world are complicated but are made of the simplest materials and act according to the most fundamental law. The Book of Changes, one of the Confucian classics, maintains that in the universe there are two kinds of qi: yang and yin. Both are contradictory and unified. Integrated, they can produce everything in the world. Simplicity makes people easy to understand and obedient, and makes all things in the world rational.

The Book of Rites, another Confucian classic, says the most popular music is plain and the greatest rite is simple. Both can bring into full play the role of aesthetics and education.

Laozi, the classic of Taoism, says that the Tao (Way) exerts a unified power which splits into two opposite aspects. Then, a third thing is produced, which in turn produces the myriad things. This classic says the strongest voice seems to be no voice, and the most vivid image seems to be no image. Such thoughts are expressed in various kinds of traditional Chinese arts.

Traditional Chinese opera (such as Peking Opera) has a simple technique of expression. On the stage, there is no setting at all, and few props, except for a desk and a chair or two. There is no real door or carriage for an actor or actress to open and close or sit in. Three or four steps represent a long journey, and six or seven persons represent a large army. The actors and actresses stir the imagination of the viewers with their movements, leading them to imagine that the performers are rowing a boat, sitting in a sedan chair or shooting a wild goose. To display the world in simple colors and lines is a principle of Chinese painting. Especially in freehand brushwork, the painter seeks after the spirit of the image, the things in his mind and the things he understands, instead of sophisticated images. With just a hint, he passes on the posture and image of the thing in his mind. What he wants to convey to the viewer is not his sharp and careful observation and mimicry, but his great imagination, creativity and rich feelings. Expressing things in a vague way usually has a stronger appeal.

Ni Zan of the Yuan Dynasty was a powerful promoter of the simple painting style. His landscape paintings have little brushwork and few figures. His paintings are elegant and simple but attractive, and had a great influence on later generations.

The beauty of conciseness. This is clearly illustrated in classical Chinese poems. Chinese lyric poems are famous for their short and concise lines. Like the montage technique used in film shooting, these lines can link separate pictures to achieve a strong effect.

The marble steps with dew turn cold,

Silk soles are wet when night grows old.

She comes in, lowers the crystal screen,

Still gazing at the moon serene.

The above poem, titled Standing Grievously by Li Bai, a great poet of the Tang Dynasty, describes the sleepless night of a maid of honour in imperial palace in 20 characters. Without the character of complaint, the poem is sad and moving.

Homeward I cast my eyes; long, long the road appears;

My old arms tremble and my sleeves are wet with tears.

Meeting you on a horse, I have no means to write.

What can I ask you but to tell them I’m all right?

This four-line poem, titled On Meeting a Messenger Going to the Capital, written by Cen Shen, another leading Tang poet, tells of his experience stationed at a remote garrison outpost.

Western poems, by contrast, tend to be longer and wordier. These differences stem from differences in cultural viewpoints and the traditional literary outlooks of the Oriental and Western peoples. Western people attach great importance to the differences between concrete things, and Western literature focuses on reproduction and imitation of things, and emphasizes unique and fantastic plots. Chinese traditional culture focuses on people and exchange of thought, while Chinese literature emphasizes expression of the author’s emotions. This is why a poem containing only 20-odd words can be passed down from ancient times and retains its popularity.

Calligraphy is the simplest artistic endeavor, being composed merely of black dots and strokes. The integration, distribution and change of lines create various kinds of charm in a simple, easy, implicit and symbolic artistic means of expression.

Ancient calligraphy critics spoke highly of the functions of expressing beauty and lyrics that simple and concise strokes had, and explained the reasons. Zhong You, of the late Eastern Han Dynasty, pointed out in one of his articles on calligraphy: “Handwriting is a dividing line composed of dots and strokes, but the beauty expressed by handwriting is produced by persons, and is an outer expression of the aesthetics and ideals of those persons.”

In an article titled On Written Language, Zhang Huaiguan, of the Tang Dynasty, says, “To express an idea in written language several characters or sentences are needed. But in calligraphy, one character can express the whole soul of the calligrapher. This is the essence of simplicity.” The simplicity and conciseness of calligraphy are its enchanting characteristics. No complicated tools are needed for calligraphy – just paper, brush, ink stick and ink slab. Also, the characters are for the most part those still used today. Calligraphy is simple, but it is not easy to master. It is difficult to have a good command of creating a whole calligraphic work which is composed of lines of individual characters. It is very difficult to handle well the relations between the individual characters and the whole work. Calligraphy is like an acrobat’s performance of balancing on a monocycle, and the acrobat has to keep his balance through a sixth sense. The handwriting technique is easy to learn, but difficult to master.

The beauty of momentum and rhythm. The Book of Changes says, “Energy gathers into visible things.” Zhuangzi, another famous Taoist book, says, “Human beings live on the gathering of energy. Gathering of energy makes survival of human beings. Human beings die as energy is dispersed.”

In works on calligraphy, momentum means the qualities, characters and vitality of calligraphic works. This is one of the basic elements of the beauty of calligraphic works. In his article on momentum of hand writing, Cai Yong of the Eastern Han Dynasty, the earliest calligraphy critic, says, “Yang (masuline and positive) and yin (feminine and negative) bring calligraphic works vigorous.”

Rhythm is different from momentum or energy, and describes a pleasing sound. In the case of handwriting, it means well-arranged dots and strokes forming a harmonious, beautiful, powerful and rhythmical calligraphic work. The momentum and rhythm of handwriting are like a chemical reaction. Momentum reflects the beauty of the visible structure of characters which change frequently and demonstrate the special technique and ability for expression of the calligrapher, while rhythm reflects the style and the way to illustrate the emotions and feelings of the calligrapher, or the power of understanding, imagination and creation. As Sun Guoting puts it in his famous Treatise on Calligraphy: “Great changes take place at the tip of the writing brush” and “rhythm is reflected on the paper ” to describe the momentum and rhythm of the handwriting. Rhythm and momentum exist together, are linked together and are the two sides of the same coin, with different designs.

Liu Xizai, a literature and art critic of the Qing Dynasty, spoke highly of the beauty of rhythm and momentum of calligraphy. In his General Introduction to Literature and Art · General Introduction to Calligraphy, he says, “Rhythm means expression of emotions and feelings, and momentum means quality and style. Without rhythm and momentum it is not calligraphy.” He further talked about the relations between calligraphy and personal accomplishment. He said that rhythm and momentum are expressions of the mind of the calligrapher; otherwise, the calligraphic work is a bad one, just a copy. He emphasized that handwriting should be natural and should reflect the calligrapher himself. Only when the quality of the calligrapher is purified, can the calligrapher create a rhythmic and vigorous calligraphic work.

![]() The beauty of moderation. Moderation is a Confucian theory and a moral standard. According to The Book of Rites, moderation can make everything in the world grow. Taoism emphasizes harmony as above everything, and advocates that the people should purify the original features of nature. In literary and artistic creation, the beauty of moderation means a controlled expression of emotions, and a harmonious and suitable treatment of the relations between the emotions of the artist and the objects and environment around, a harmonious integration of the subject and object.

The beauty of moderation. Moderation is a Confucian theory and a moral standard. According to The Book of Rites, moderation can make everything in the world grow. Taoism emphasizes harmony as above everything, and advocates that the people should purify the original features of nature. In literary and artistic creation, the beauty of moderation means a controlled expression of emotions, and a harmonious and suitable treatment of the relations between the emotions of the artist and the objects and environment around, a harmonious integration of the subject and object.

Sun Guoting was the first to include moderation as one of the aesthetic criteria and guiding principles of calligraphic works. Sun believed that moderation meant the coordination and reunification of the various kinds of organic elements of calligraphy. He confirmed the harmony of calligraphy as reflecting materials while expressing the emotions of the calligrapher. Calligraphic creation is a natural exposure of people’s emotions. But such exposure should be mediatory, controlled and harmonious, in order to bring into one line the beauty of nature and the beauty of personality.

Later, many calligraphers made further explanations of the beauty of moderation through their own understanding and practice. They emphasized that calligraphers naturally demonstrate their emotions and feelings through their unrestrained and vigorous handwriting. But if they can control the exposure of their emotions and feelings, their calligraphic works express the beauty of moderation, which can reach even a higher level.

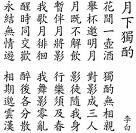

Wang Duo of the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties was a good example in this respect. He made breakthroughs in his handwriting, and sought after novelty, especially in his cursive-script works. In his words, characters are like acrobatic movements in the air. But he controlled his characters in the lines. For example the characters in his Vertical Scroll of Poem by Gao Shi on the left page are vigorous and flying, reaching the highest level of the beauty of moderation.

Yang Weizhen of the Yuan Dynasty was not influenced by the long-standing calm and gentle style represented by Zhao Mengfu, and developed the ![]() unique style named after him. In On Donations to Zhenjing Nunnery (on the bottom of the page) by him in the running script, some characters are big and some small, some are dry and some wet, and some are in the regular script and some in the cursive script. Also, some characters are in the classical style. The characters are changeable, but integrated. This is an excellent example of the beauty of calligraphic moderation.

unique style named after him. In On Donations to Zhenjing Nunnery (on the bottom of the page) by him in the running script, some characters are big and some small, some are dry and some wet, and some are in the regular script and some in the cursive script. Also, some characters are in the classical style. The characters are changeable, but integrated. This is an excellent example of the beauty of calligraphic moderation.

Zheng Banqiao of the mid-Qing Dynasty was one of the “eight unusual geniuses of Yangzhou,” and was famous for his unique calligraphic style. He was once a county magistrate, but he offended his superior and left his post. He went back to his hometown, and lived by selling his paintings and calligraphic works. He would use several different scripts in one work. Any page from his running-script booklet includes characters written in the official, cursive and running scripts. Some characters are in the styles of Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi, or in the vigorous style which appears on Han steles, or in the free wild cursive script. His handwriting features great changes. However, they are not disordered, but harmonious. Zheng Banqiao was fond of painting bamboo, rocks and orchids. He painted orchids like writing characters, and wrote characters like painting orchids.