Archive for the ‘Chinese Festivals’ Category

Folk Arts and Festivities-Chinese New Year

Chinese New Year, also known as the Spring Festival, is the biggest holiday in China. Recorded in Li Ji – Yue Ling, Chinese New Year is the time when “air pressure of the sky comes down and air pressure of earth goes up. When heaven and earth connects, all things geminate.” This summarizes the main features of folk art works on Chinese New year, which are heaven and earth, yin and yang, propagation and harvest.

Chinese New Year window decoration usually bears the same implication as for wedding ceremonies. The best I have seen is the paper-cut on the cave windows on the loess plateau. On New Year’s Eve, people put on brand new white window liner. Above the crossbar of the cave window is considered the sky. On the center of the crossbar is a large ball flower of “Baby with coiled hair holding a pair of fish,” a “Revolving flower ” indicating that life revolves around the sky. Below the crossbar is the 36 window lattice. A totem animal (a tiger or a deer) takes the middle four lattice, and other window decorations fill the rest to form a diamond square design with end flowers on four corners. It is similar to the “Thirty-six window lattice of clouds” on wedding occasions, or the “Eight diagram window.” Themes of those paper-cuts include “Two dragons playing with a ball,” “Two phoenixes playing around a peony;” “A golden clock over a frog;” “A deer and a crane;” “A snake twining round a rabbit;” “A vulture catching a rabbit;” “A dragon, a tiger and a vulture;” “Lion playing with a silk ball;” “A rooster holding a fish in the mouth;” “A rat bit open the sky;” “A bowl of Pomegranate;” “Buckled bowl in the shape of two frogs;” or of two fish, two tigers or two rats, “Fairy fish vase;” “Paired tiger vase;” “The Eight diagram fish;” “Deer head” etc. There are also a variety of paper-cuts with the theme of life and propagation: “A snake twining round nine eggs;” “treasure toad;” “A pair of toad;” “frog carrying a rock.” It is a colorful picture of a legendary animal kingdom with birds flying, fish jumping, people laughing and horse soaring. Inside the cave, the kang is decorated with “Border flowers,” across the dish rack is a row of “Dish rack clouds,” and in the center of the ceiling is a large ball flower of “Phoenix playing around peony,” and on the lintel is “Baby holding hands” or “Baby of sun flower seed.”

In Shandong, the lower stream of the Yellow River, it is a whole different taste. The main subject of Chinese New Year paper-cut is the flower of life which grows high from a water pot or a fish bowl. Paper-cuts of the flower of life in a water vase, or the tree of life in a water pot, are pasted across the lintel. Similar paper-cut is also popular in northern Suzhou, south of the Yellow River, all the way to the Yangtze River valley.

In Shandong, the lower stream of the Yellow River, it is a whole different taste. The main subject of Chinese New Year paper-cut is the flower of life which grows high from a water pot or a fish bowl. Paper-cuts of the flower of life in a water vase, or the tree of life in a water pot, are pasted across the lintel. Similar paper-cut is also popular in northern Suzhou, south of the Yellow River, all the way to the Yangtze River valley.

Nowadays urban residents like to paste Chinese New Year paper-cut letter “Fu” (good fortune) upside, as “fu dao” (good fortune arrives). Actually, the diamond square of upside down letter “Fu” was meant to be a rotating symbol for perpetual life.

In Inner-Mongolia, Chinese New Year door-god paper-cut is a pair of deer or a pair of roosters. In central Shaanxi, it is two tigers, and in Henan two monkeys, or cows, or two babies with coiled hair riding a golden cow. These paper-cuts are made with yellow glossy paper, a common way to pray for patronage from the totem or legendary animals for family safety and keeping away evil spirits and disasters.

Chinese New Year is the “beginning of a year, everything starts fresh and gay.”Every household changes a new woodcut of New Year picture. Polytheism that has been widely accepted by Chinese folks believes that every living creature has a power of its own. Such belief can be seen in some of the art works too. New Year picture featuring all types of gods are put out at Chinese New Year time for safeguard. On the 23rd of the twelfth lunar month is to worship the cooking stove, replacing a year old woodcut of “stove god” with a new one for the New Year. Pasted on the two door leaves are two famous warriors from the Tang dynasty, door god “Shentu” and “Yulei,” carrying reed ropes ready to kill any approaching demons. On the shrine by the door steps is god of land; in the yard are gods from ten directions; above the stove is god of wealth; and by the well is god of the well. In Yunnan, Yi and Bai ethnic groups culture has over 100 different images of gods for safeguard, each having a designated function.

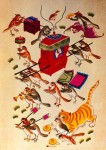

7th of the first Lunar month is the “Human Day,” the day the rat, god of propagation, marring off a daughter. Women would hide their basket of needlework to avoid being bitten by the rat. Big paper-cut “Rat marrying off a daughter” can be seen on the wall in every household on the Human Day. Other areas where birds are worshipped, like Sichuan, it is the “Sparrow marring off a daughter.” The 15th of the first lunar month is the Lantern Festival. Every household folds paper lanterns in a square or a diagram shape, fully decorated with colorful paper-cuts. Types of the lanterns vary from geographically related legendary animals to geometry symbols of life and propagation, such as “The moon lantern;” “Baby with coiled hair lantern;” “The eight diagram lantern,” to name a few.

In the south of Yangtze River valley, between 1st-15th of the first lunar month, people have large gatherings to invite, dance for, and send off exorcists. It starts with going to an exorcist temple to request the mask of exorcist for a baptismal ritual. In Miao ethnic group area, it is the Chinese New Year outdoor gathering in the countryside, when young men and women in festival customs bearing embroidery totem animals and life symbols, playing music instrument (a toad shaped wind instrument), singing and dancing. Such festivity is actually a cultural extension from the ancient custom of worshipping heaven and earth at the suburb of the capital.

Dragon Boat Festival

Double Fifth Festival, is celebrated on the fifth day of the fifth moon of the lunar calendar. It is one of the most important Chinese festivals.

Double Fifth Festival, is celebrated on the fifth day of the fifth moon of the lunar calendar. It is one of the most important Chinese festivals.Dragon Boat race: Traditions At the center of this festival are the dragon boat races. Competing teams drive their colorful dragon boats forward to the rhythm of beating drums. These exciting races were inspired by the villager’s valiant attempts to rescue Chu Yuan from the Mi Lo river. This tradition has remained unbroken for centuries.

Tzung Tzu (Pinyin: Zong-Zi): A very popular dish during the Dragon Boat festival is tzung tzu. This tasty dish consists of rice dumplings with meat, peanut, egg yolk, or other fillings wrapped in bamboo leaves. The tradition of tzung tzu is meant to remind us of the village fishermen scattering rice across the water of the Mi Low river in order to appease the river dragons so that they would not devour Chu Yuan.

Ay Taso (Pinyin: Ai-Cao): The time of year of the Dragon Boat Festival, the fifth lunar moon, has more significance than just the story of Chu Yuan. Many Chinese consider this time of year an especially dangerous time when extra efforts must be made to protect their family from illness. Families will hang various herbs, called Ay Tsao, on their door for protection. The drinking of realgar wine is thought to remove poisons from the body. Hsiang Bao are also worn. These sachets contain various fragrant medicinal herbs thought to protect the wearer from illness.

The Spring Festival

The Spring Festival is the most important festival for the Chinese people and is when all family members get together, just like Christmas in the West. All people living away from home go back, becoming the busiest time for transportation systems of about half a month from the Spring Festival. Airports, railway stations and long-distance bus stations are crowded with home returnees.

The Spring Festival is the most important festival for the Chinese people and is when all family members get together, just like Christmas in the West. All people living away from home go back, becoming the busiest time for transportation systems of about half a month from the Spring Festival. Airports, railway stations and long-distance bus stations are crowded with home returnees.

The Spring Festival falls on the 1st day of the 1st lunar month, often one month later than the Gregorian calendar. It originated in the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600 BC-c. 1100 BC) from the people’s sacrifice to gods and ancestors at the end of an old year and the beginning of a new one.

Strictly speaking, the Spring Festival starts every year in the early days of the 12th lunar month and will last till the mid 1st lunar month of the next year. Of them, the most important days are Spring Festival Eve and the first three days. The Chinese government now stipulates people have seven days off for the Chinese Lunar New Year.

Many customs accompany the Spring Festival. Some are still followed today, but others have weakened.

Store owners are busy then as everybody goes out to purchase necessities for the New Year. Materials not only include edible oil, rice, flour, chicken, duck, fish and meat, but also fruit, candies and kinds of nuts. What’s more, various decorations, new clothes and shoes for the children as well as gifts for the elderly, friends and relatives, are all on the list of purchasing.

Before the New Year comes, the people completely clean the indoors and outdoors of their homes as well as their clothes, bedclothes and all their utensils.

Then people begin decorating their clean rooms featuring an atmosphere of rejoicing and festivity. All the door panels will be pasted with Spring Festival couplets, highlighting Chinese calligraphy with black characters on red paper. The content varies from house owners’ wishes for a bright future to good luck for the New Year. Also, pictures of the god of doors and wealth will be posted on front doors to ward off evil spirits and welcome peace and abundance.

The Chinese character “fu” (meaning blessing or happiness) is a must. The character put on paper can be pasted normally or upside down, for in Chinese the “reversed fu” is homophonic with “fu comes”, both being pronounced as “fudaole.” What’s more, two big red lanterns can be raised on both sides of the front door. Red paper-cuttings can be seen on window glass and brightly colored New Year paintings with auspicious meanings may be put on the wall.

People attach great importance to Spring Festival Eve. At that time, all family members eat dinner together. The meal is more luxurious than usual. Dishes such as chicken, fish and bean curd cannot be excluded, for in Chinese, their pronunciations, respectively “ji”, “yu” and “doufu,” mean auspiciousness, abundance and richness. After the dinner, the whole family will sit together, chatting and watching TV. In recent years, the Spring Festival party broadcast on China Central Television Station (CCTV) is essential entertainment for the Chinese both at home and abroad. According to custom, each family will stay up to see the New Year in.

Waking up on New Year, everybody dresses up. First they extend greetings to their parents. Then each child will get money as a New Year gift, wrapped up in red paper. People in northern China will eat jiaozi, or dumplings, for breakfast, as they think “jiaozi” in sound means “bidding farewell to the old and ushering in the new”. Also, the shape of the dumpling is like gold ingot from ancient China. So people eat them and wish for money and treasure.

Southern Chinese eat niangao (New Year cake made of glutinous rice flour) on this occasion, because as a homophone, niangao means “higher and higher, one year after another.” The first five days after the Spring Festival are a good time for relatives, friends, and classmates as well as colleagues to exchange greetings, gifts and chat leisurely.

Burning fireworks was once the most typical custom on the Spring Festival. People thought the spluttering sound could help drive away evil spirits. However, such an activity was completely or partially forbidden in big cities once the government took security, noise and pollution factors into consideration. As a replacement, some buy tapes with firecracker sounds to listen to, some break little balloons to get the sound too, while others buy firecracker handicrafts to hang in the living room.

The lively atmosphere not only fills every household, but permeates to streets and lanes. A series of activities such as lion dancing, dragon lantern  dancing, lantern festivals and temple fairs will be held for days. The Spring Festival then comes to an end when the Lantern Festival is finished.

dancing, lantern festivals and temple fairs will be held for days. The Spring Festival then comes to an end when the Lantern Festival is finished.

China has 56 ethnic groups. Minorities celebrate their Spring Festival almost the same day as the Han people, and they have different customs.

Mid-Autumn Festival

Time: Always On the 15th Day of the 8th Month by the Chinese Lunar Calendar

Time: Always On the 15th Day of the 8th Month by the Chinese Lunar Calendar

Venue: All over China

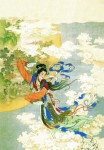

Origin: During the Zhou Dynasty (16th-11th centuries BC), the night of the full moon was an occasion for the Chinese to hold rituals to greet the cool weather and sacrifice to the Goddess of the Moon. By the Tang Dynasty (618-907) moon-watching and merry-making had become part of the ritual. During the Northern Song (960-1127), the 15th day of the 8th lunar month was designated as Mid-Autumn Festival. When night falls, the orb of the moon hangs full in the firmament, shedding a flood of silvery light over the land, while family members in China gather for the happiness of reunion, munching moon cakes and marveling at the chastened glory of the  Goddess of the Moon. By Chinese custom the 15th day of the 8th lunar month is a day for family reunion as symbolized by the full moon and the moon cake.

Goddess of the Moon. By Chinese custom the 15th day of the 8th lunar month is a day for family reunion as symbolized by the full moon and the moon cake.

What’s On: Ceremonies to make libation and sacrifices to the moon, and watching the moon while enjoying moon cakes. There is always something dream-like and romantic about Mid-Autumn Festival, on account of its close association with such Chinese fables as Chang’e fleeing to the moon, the man Wu Gang performing the unending servitude to cutting an osmanthus tree, and the Jade Rabbit pounding medicinal herbs with a pestle. For men of letters the festival is an occasion to get together, improvise poems over a cup of wine and recite them to each other.