Archive for the ‘Peking Opera’ Category

Four Roles of Peking Opera:Sheng, Dan,Jing and Chou

Peking Opera features “character categorization.” In accordance with gender and disposition, characters are divided into four basic roles: sheng (male character type), dan (female character type), jing (character type with a painted face), and chou (a clown). Each role type comes with its own subdivision.

subdivision.

Sheng is a grown-up male. It can be further divided into four types. First, lao sheng playing middle-aged or old men with beard. A lao sheng can be of a type specializing in singing, or a type specializing in martial arts. Lao sheng is the most common male character in Peking Opera. Cheng Changgeng and Tan Xinpei, regarded as founders of Peking Opera, were both lao sheng players. Second, wu sheng, or man with martial skills. A wu sheng can specialize in long weapons or short weapons. The long-weapon wu sheng wears armor, looks dignified and has a moderate skill of singing and recitation, whereas the short-weapon wu sheng wears short clothes and is swift of action. Third, xiao sheng playing young handsome men, most of whom are scholars. This character is frequently portrayed in love stories. Xiao sheng can be further divided into gauze-hat sheng (a court official), fan xiao sheng (scholar using a fan), pheasant-feather fan sheng (a handsome young man), and a poor sheng (a scholar failing to become an official). And fourth, hong sheng playing characters with a red face such as Guan Yu and Zhao Kuangyin.

Owing to the uniqueness of Peking Opera, the role of xiao sheng had long been relatively unimportant. While many plays give prominence to lao sheng and dan (female) roles, xiao sheng is relatively obscure. In the history of Peking Opera, well-known actors playing the xiao sheng role were few in number. Earlier acclaimed xiao sheng players were Cheng Jixian (1874-1944), Jiang Miaoxiang (1890-1972) and Jin Zhongren (1886-1950). Later renowned players were Yu Zhenfei (1902-1993) and Ye Shenglan (1914- 1978). Among xiao sheng impersonators, the only one able to play in shows xiao sheng is the hero was Ye Shenglan.

This is quite different from Western operas where the young hero is very important and is played by highly acclaimed actors. In performance, xiao sheng’s most striking feature is singing and recitation with a combination of real and false voices. His falsetto is relatively high-pitched and fine, making the role distinctively different from lao sheng. On the other hand, xiao sheng’s falsetto is different from that of the dan (female) role. It should be strong but not rough. And it should not be as soft and gentle as a woman’s voice. Fine-tuning nuances in a xiao sheng’s singing is difficult. This is why not many actors have excelled in playing this role like Ye Shenglan.

Dan is a general term for female characters. The gentle and quiet is called qing yi and usually represents orthodox yong women. The vivacious is called hua dan and represents girls of ordinary households or extroversive disposition. There are also lao dan (old female), wu dan (female with martial skills) and cai dan which used to be played by male actors. Only “painted face,” or jing, usually has facial makeup. They are all male with a rough, bold and uninhibited character. They speak loudly, shout at the slightest provocation and, if irritated, may use force. The jing roles are divided, too, into the “Singing-oriented” type, or wen jing, and the “martial” type, or wu jing. Actors impersonating jing commonly paint their faces in various styles that range from a single color to be wildering combinations and patterns.

Read the rest of this entry »

The Stage and Props of Peking Opera

In an early period, Peking Opera was staged on an interesting stage. The front of the stage extends forward, with three sides facing the audience. The other side is the backstage. An embroidered curtain hangs across the backstage, and on each side of the curtain is a curtained door for performers to enter or exit the stage. Coming onto the stage from the entrance door, an actor with full makeup and costume begins to play his role; at the conclusion of his performance, he goes off the stage through the exit door. This means the end of a show or transition into another part of a play. After 1908, which saw the appearance of modern theaters and the use of setting in Shanghai, people called the old-style stage curtain shoujiu.

of the stage extends forward, with three sides facing the audience. The other side is the backstage. An embroidered curtain hangs across the backstage, and on each side of the curtain is a curtained door for performers to enter or exit the stage. Coming onto the stage from the entrance door, an actor with full makeup and costume begins to play his role; at the conclusion of his performance, he goes off the stage through the exit door. This means the end of a show or transition into another part of a play. After 1908, which saw the appearance of modern theaters and the use of setting in Shanghai, people called the old-style stage curtain shoujiu.

Shoujiu was made of cloth or satin and embroidered with exquisite patterns. It served as setting but was not limited by operas being performed. It was more like a leading actor’s signboard. Every famous actor had his representative shoujiu. Mei Lanfang (1894-1961), for example, used a curtain embroidered with plum blossoms, peonies and peacocks; and Ma Lianliang (1901-1966), a well-known actor who usually played old people, had a stage curtain embroidered with a set of Han Dynasty horsedrawn chariots.

Shoujiu was made of cloth or satin and embroidered with exquisite patterns. It served as setting but was not limited by operas being performed. It was more like a leading actor’s signboard. Every famous actor had his representative shoujiu. Mei Lanfang (1894-1961), for example, used a curtain embroidered with plum blossoms, peonies and peacocks; and Ma Lianliang (1901-1966), a well-known actor who usually played old people, had a stage curtain embroidered with a set of Han Dynasty horsedrawn chariots.

On the stage are placed props of a decorative nature, usually a table and two chairs. An imaginary room comes with the presence of a table and two chairs. In the mind of the audience, the space around the table and chair may be a palace, a study, a court where suspects are tried, or a military commander’s tent. Or it can be a boisterous restaurant. The difference lies in details in the decoration of the table and chairs. If it is a palace, the table curtain will have dragon patterns; if it is a study, the table curtain will be of a light blue or light green color and embroidered with several orchids.

A lot of learning goes into how to place the table and chair. If the chair is placed behind the table, it shows a solemn occasion: an emperor holds court, an official officiates, or a general handles military affairs. If the chair is placed in front of the table, it shows an ordinary household’s daily life.

There is another interesting point. Chairs on the stage all have cushions, which are of different thickness. Why? In Peking Opera, different characters wear shoes with soles of different thickness. A sheng or jing character wears thick-soled shoes (as thick as 20cm), whereas dan and chou characters wear thin-soled ones (1-2 cm). And different characters are required to have different sitting postures. A dan character should really sit on the cushion; whereas a sheng character should sit on the edge of the chair; and a chou (clown) character may move about or even squat on the cushion. The table can serve as a bed, a support for observing a distant object from a great height, a bridge, a gate tower, a mountain, or even a cloud. The chair can serve as a weapon for characters. In Peking Opera, such a simple method is used to portray a rich plot. When enjoying Peking Opera, it is not necessary to seek realness. Audiences are given great room for imagination. “A table and two chairs” has become a symbolic mark of Peking Opera’s “less is more” way of portrayal.

Characters in Peking Opera often ride horses. Audiences will not see a real horse on the stage. Instead, a character holds a riding whip with tassels to show he is on a horse. This is another example of the extensive use of symbols in Peking Opera. There is not a real horse on the stage, but the actor has to portray his riding posture in a distinctive and graceful way. A riding whip gives an actor the greatest freedom for acting. With different pantomimic gestures with the whip, he can show a galloping horse, a horse with a drooping head, a horse that remains at the same place after running for half a day, or a horse that has traveled thousands of miles in a twinkle.

A riding whip is a tangible stage prop. In Peking Opera there are also props of a virtual type. In Picking up a Jade Bracelet (shi yu zhuo), for example, a girl stitches a cloth shoe sole. While the sole is real and tangible, the needle is imaginary. In the hand of the actress, the absence of a needle is better than an actual needle. Another example is a dinner party. A host orders “setting the table.” Waiters immediately carry a wine pot and glasses onto the stage. The host and guests begin drinking glass after glass. But audiences do not see real wine, rice and dishes. The actors on the stage do not really drink and eat. But soon they all are “full”. In Peking Opera, kitchen utensils are not usually carried onto the stage.

Stage props, big and small, as well as simple setting in Peking Opera, including candlesticks, lanterns, oars, letters, paper, ink, writing brushes, ink slabs and pavilions, are not made of genuine materials — they play a symbolic role only. A great variety of weapons as well as flags carried by guards of honor are not real, either, though they bear a similarity to real things. A Peking Opera is usually divided into several acts. Traditionally, when there is a change of acts, a group of men called stage checkers would change the setting. Wearing long gowns but no facial expression whatsoever, they would come onto the stage after an act is over, reshuffle the table and chairs, indicating a change of place and time, and leave the stage in silence. Sometimes, they would produce some stage effect. In Inter-linked Military Tents (lian ying zai), for example, to show Liu Bei making his escape in a conflagration, a stage checker standing on the side of the stage would light pieces of paper and throw the burning paper onto the actors, who thereupon do escaping or extinguishing acts — feats worthy of acrobats.

Traditional stage setting is part of Peking Opera’s conventions. Many foreign audiences are very curious about Peking Opera’s highly stylized performances. In Peking Opera, two pieces of cloth represent a sedan chair; a push and a pull by an actor means opening and closing a window. People watching Peking Opera for the first time may find it difficult to understand. Also, Peking operas are closely connected with the history, customs, culture and social conditions of China. To enjoy Peking Opera, audiences need to understand China, its his tory and culture.

Today, a big silk curtain hangs before a Peking Opera stage. A show begins when the curtain rises. This curtain does not come down until the whole show comes to an end. Between acts, a second curtain made of satin rises and closes. This “double curtain” practice is the result of a reform in the 1950s when the reshuffle of table and chairs on the stage between acts by a group of checkers in full view of the audience was abolished.

The Art of Listening, Old-style Theaters

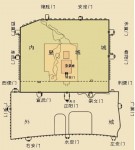

Old Beijing with the Forbidden City at its center. The Outer City in the south is where old-style theaters were concentrated. In the past, people visiting Beijing would invariably go to a theater to see a Peking Opera performance. When we see a show today, we say “watch an opera.” But old Beijingers say “listen to an opera” instead. What counts in Peking Opera is singing, whereas performance is highly stylized. Audiences are wont to listen to singing with eyes shut and hands beating time. When they like a particular line, they would shout “bravo!” These are typical fans.

Old Beijing with the Forbidden City at its center. The Outer City in the south is where old-style theaters were concentrated. In the past, people visiting Beijing would invariably go to a theater to see a Peking Opera performance. When we see a show today, we say “watch an opera.” But old Beijingers say “listen to an opera” instead. What counts in Peking Opera is singing, whereas performance is highly stylized. Audiences are wont to listen to singing with eyes shut and hands beating time. When they like a particular line, they would shout “bravo!” These are typical fans.

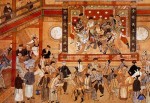

Old-style theaters where Peking Opera was performed before the 1950s were called xiyuanzi, which literally means “opera courtyard.” Facilities in a xiyuanzi were rather simple. The stage was square, with three sides extending right into rows of seats for the audience. At an early date in the Qing period (1644-1911), xiyuanzi was called “tea courtyard.” At the time, audiences paid for the tea but not the opera they watched. For customers, their main purpose in coming to the “tea courtyard” was to drink tea, whereas watching an opera was sort of “incidental.” In the Qing period, a show in a xiyuanzi could last as long as 10-12 hours, all in the daytime. Customers also paid for snacks such as sunflower seeds and roasted peanuts. Tea charge was not charged until before the start of the last but one item on the day’s theatrical program. A striking feature of xiyuanzi in old Beijing was “hot towel throw.” Waiters, shouting “here comes the towel,” would throw steaming towels to audiences, with great accuracy. Waiters accepted tips and never haggled over their size. Tianqiao area in Beijing used to be a center of folk culture”

“Tea courtyards” were later called xiyuanzi, or old-style theater. In the period of the Republic of China (1911-1949), they became known as theaters, and the stage was patterned after stages in the West. Xiyuanzi, which was of a traditional architectural style, was smaller than a typical Western theater in capacity, but what audiences heard in a xiyuanzi was original singing of actors and actresses, free of a loudspeaker.

In the middle and latter periods of the 19th century, as Peking Opera gained popularity, the number of xiyuanzi in Be?ing increased, and most of them were located in a flourishing commercial district south of the Qianmen Gate Tower. Viewed from above, the district is situated on the city’s north-south axis. The stage in an old-style theater was not big. Stages were first paved with wooden planks and later covered with carpets. This was to make sure that actors making summersaults would not hurt themselves. At the stage front were usually erected two columns on which were written words in praise of a troupe performing at the time. In the rear of the stage hung an embroidered curtain, which was the private property of the leading actor of the day. The curtain bore patterns of flowers and birds, in a style compatible with the leading actor. Seeing the curtain, audiences knew who was going to play the lead.

The photo of the mural was taken during the Republic of China period (1911-1949). Photo by courtesy of Mei Lanfang Museum. Below the stage was dirt ground. Later, ground was paved with bricks and still later with cement. In an early period, audiences sat on benches facing one another across oblong wooden tables. This sitting posture facilitated chatting and eating snacks but was not suitable for watching a theatrical performance. It is not until after 1914 that long benches with back support were placed parallel to the stage, enabling audiences to face the stage. On the back of the benches were nailed long- framed planks, on which were placed teacups. At the time, men and women were separated at old-style theaters, with men sitting downstairs and women sitting upstairs. It is not until 1931 that men and women sat together. At the back of the rows of seats was usually placed an oblong table with the sign “The Suppression Seat” on it. When a play started, fully-armed soldiers came to sit behind the table to deal with any possible commotion. On a holiday the theater owner would hand them envelopes stuffed with money to seek their protection.

The photo of the mural was taken during the Republic of China period (1911-1949). Photo by courtesy of Mei Lanfang Museum. Below the stage was dirt ground. Later, ground was paved with bricks and still later with cement. In an early period, audiences sat on benches facing one another across oblong wooden tables. This sitting posture facilitated chatting and eating snacks but was not suitable for watching a theatrical performance. It is not until after 1914 that long benches with back support were placed parallel to the stage, enabling audiences to face the stage. On the back of the benches were nailed long- framed planks, on which were placed teacups. At the time, men and women were separated at old-style theaters, with men sitting downstairs and women sitting upstairs. It is not until 1931 that men and women sat together. At the back of the rows of seats was usually placed an oblong table with the sign “The Suppression Seat” on it. When a play started, fully-armed soldiers came to sit behind the table to deal with any possible commotion. On a holiday the theater owner would hand them envelopes stuffed with money to seek their protection.

During the early stage of xiyuanzi, there were no newspapers, nor were there ads and posters. The method of promotion was to place at the xiyuanzi gate stage properties for the evening’s show. For people who loved Peking Opera, a look at the stage properties was enough for a guess at what the show was for the evening. For example, a block of stone pointed to The Yanyang Building (yan yang lou) and a big spear Battling Down-sliding Chariots (tiao hua che). A heap of weapons of different kinds indicated that the evening’s last play would be Havoc in Heaven (nao tian gong). The weapons were used to subdue the Monkey King, hero of the play. A day’s program was printed on a piece of yellow paper with a wood block and sold for a penny or two. It is not until after the 1920s that programs were printed with lead types.

During the early stage of xiyuanzi, there were no newspapers, nor were there ads and posters. The method of promotion was to place at the xiyuanzi gate stage properties for the evening’s show. For people who loved Peking Opera, a look at the stage properties was enough for a guess at what the show was for the evening. For example, a block of stone pointed to The Yanyang Building (yan yang lou) and a big spear Battling Down-sliding Chariots (tiao hua che). A heap of weapons of different kinds indicated that the evening’s last play would be Havoc in Heaven (nao tian gong). The weapons were used to subdue the Monkey King, hero of the play. A day’s program was printed on a piece of yellow paper with a wood block and sold for a penny or two. It is not until after the 1920s that programs were printed with lead types.

Peking Opera had a close relationship with the Qianmen Gate Tower area in Beijing, which was a cradle of folk culture in the city. In the early years of Peking Opera, the Qianmen Gate Tower area was where the city’s entertainment, catering industry, commerce and people’s cultural activities were concentrated. It is right in this area that Peking Opera grew and thrived. Not only were Peking Opera’sold theaters and the homes of actors and actresses concentrated here, but many Peking Opera fans and people connected with theatrical shows lived in the area, too. In the more than 50 years from the early 20th century to 1957, the Qianmen Gate Tower area was home to some 600 famous artists of Peking Opera, pingju opera, acrobatics and quyi (folk art forms including ballad singing, story telling, comic dialogues, clapper talks and cross talks). These performing artists had learned their art from different masters and each had his unique skill. At the time, Tianqiao south of the Qianmen Gate Tower was a thriving, densely populated downtown area of Beijing. And Tianqiao’s soul was Beijing’s traditional folk culture.

dialogues, clapper talks and cross talks). These performing artists had learned their art from different masters and each had his unique skill. At the time, Tianqiao south of the Qianmen Gate Tower was a thriving, densely populated downtown area of Beijing. And Tianqiao’s soul was Beijing’s traditional folk culture.

Anhui Troupes and the Birth of Peking Opera

Rulers of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) all liked operas. Some of them, such as Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908), were connoisseurs of Peking Opera. At the end of the 18th century, operatic singing in China had developed into several systems. Popular local operas used tunes that included gaoqiang (pitched singing), geyang (prevalent along the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze), bangzi (prevalent along the Yellow River valley) and liuzi (which originated in Shandong). To literati at the time, these operas were far inferior to kunqu opera, which is refined and serious. With much disdain, they called these local operas huabu.

Rulers of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) all liked operas. Some of them, such as Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908), were connoisseurs of Peking Opera. At the end of the 18th century, operatic singing in China had developed into several systems. Popular local operas used tunes that included gaoqiang (pitched singing), geyang (prevalent along the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze), bangzi (prevalent along the Yellow River valley) and liuzi (which originated in Shandong). To literati at the time, these operas were far inferior to kunqu opera, which is refined and serious. With much disdain, they called these local operas huabu.

The popularity of huabu had something to do with its popular appeal. Huabu plays tell historical stories or folk tales loved by the laboring people. Singing was lucid, lively and intense, and recitations were easy to understand. The ugly ducklings became so popular that many huabu companies competed for turf even in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, the birthplace of kunqu opera.

Peking Opera has its origin in huabu operas. It was not born in Be?ing (Peking). Its predecessor was a huabu opera that was prevalent in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze performed by Anhui troupes in the mid-17th century. Anhui troupes had not been limited to staging Anhui huabu opera. They also performed kunqu opera, Hubei’s hanxi opera and the central plain’s bangzi opera. As a result, these troupes had rich and colorful tunes as well as a wide range of interesting plays. Their actors had developed feats and stunts. Before coming to Beijing, the Auhui huabu opera combined the characteristics of tunes of er huang and xi pi, the former is steady and melancholy, the latter is brisk and lively, er huang and xi pi constitute the core of the tune of Peking Opera. In addition, the Anhui troupes were good at assimilating the performing characteristics of other operas, such as the recitation of jingqiang opera (Peking), the high-pitched arias of qinqiang opera (Shaanxi), the tunes and recitation of hanxi opera (Hubei), and the bodily movements, ways of portrayal and music of kunqu opera (Suzhou). After sixty years of evolution, a unique theatrical variety – Peking Opera – came into being.

In 1790, an Anhui troupe headed by Gao Langting came to Be?ing to participate in performances in celebration of the 80th birthday of Emperor Qianlong. It was soon followed by three other theatrical companies from Anhui – Sixi, Chuntai and Hechun. After doing their job, these Anhui troupes stayed in the capital to offer performances to the local public. By this time, what the Anhui troupes were offering was Peking Opera.

Peking Opera, which had been developed from an assortment of rural shows, had a wide range of audiences. They included not only members of the royal family, officials and scholars, but also merchants, townspeople and handicraftsmen. Peking Opera gradually became a townspeople-oriented performing art. The Qing Dynasty was in a period of social stability and economic prosperity when the Anhui troupes brought Peking Opera to the capital city. At the turn of the 19- 20th centuries when Peking Opera had come to maturity, Be?ing had a thriving handicraft industry and commerce; it was home to some 360 guild houses; and service industries catering to the townspeople were also thriving. At the time, the Qianmen area was not only a commercial center but also had a concentration of theaters, teahouses and restaurants; and the Tianqiao and Bell Tower areas swarmed with street performers as well as peddlers and small traders. These not only provided sources of audience for performances in the theaters but also brought new management methods for the theaters and Peking Opera companies.

After 1860, with mobile performances by opera companies, Peking Opera quickly spread all over the country. Tianjin and the surrounding Hebei and Shandong provinces were where Peking Opera gained popularity at an early date. Areas with a fairly early arrival of Peking Opera included Anhui, Hubei and northeast China. In 1867, Peking Opera spread to Shanghai. At the time, a number of well-known Peking Opera actors went south, making Shanghai a Peking Opera center on a par with Beijing. Peking Opera in Shanghai gradually developed some unique characteristics, leading later to the division of “Beijing School” and “Shanghai School.” By the beginning of the 20th century, Peking Opera was performed in Fujian and Guangdong in the south, Zhejiang in the east, Heilongjiang in the north and Yunnan in the southwest. In the 1940s, Peking Opera had impressive development in Sichuan, Shaanxi, Guizhou and Guangxi.

Portraits of Peking Opera characters played by famous actors of late Qing Dynasty, painted by Shen Rongpu, a well-known portraitist active in the late Qing period.In 1919, Mei Lanfang, a Peking Opera master actor enjoying unrivalled fame then and even today, went to Japan with his theatrical company to stage performances. Peking Opera troupes have since frequently staged performances in foreign countries. And people in the rest of the world regard Peking Opera as the representative of the traditional Chinese theater. Today, Peking Opera has become the premier opera type in China having no rival in terms of the number of plays, performing artists, troupes and audiences as well as influence.