Archive for the ‘Peking Opera’ Category

Plays that Bustle with Noise and Excitement

![]() Old timers in Beijing liked to visit temple fairs in a bygone era. They were held at different locations in the city during the Spring Festival, or the Chinese New Year, bringing great joy to children and adults alike. Peddlers sold a toy called the Golden Cudgel, a weapon used by the Monkey King, the hero in the classic novel Pilgrimage to the West. Children would buy a cudgel home and wield it the way the Monkey King was supposed to do. Of course, children could also tell one or two stories about the Monkey King and mimicked his habitual act of ear tweaking and cheek scratching.

Old timers in Beijing liked to visit temple fairs in a bygone era. They were held at different locations in the city during the Spring Festival, or the Chinese New Year, bringing great joy to children and adults alike. Peddlers sold a toy called the Golden Cudgel, a weapon used by the Monkey King, the hero in the classic novel Pilgrimage to the West. Children would buy a cudgel home and wield it the way the Monkey King was supposed to do. Of course, children could also tell one or two stories about the Monkey King and mimicked his habitual act of ear tweaking and cheek scratching.

The Monkey King is a popular opera character in China. Every Chinese likes this intelligent, resourceful, daring and just spirit, whose name is Sun Wukong. Children use the Monkey King mask and his golden cudgel to mimic his many feats.

Foreigners interested in Peking Opera are usually invited to see a Monkey King play. They will be dazzled by a group of hyperactive actors jumping and making summersaults like monkeys on the stage. The actor playing the omnipotent Monkey King will invariably leave a deep impression on the audience. The monkey play in Peking Opera comes from kunqu opera, which originated in Suzhou, east China. Today, usually male actors play the role of the Monkey King.

A performer needs to master a whole set of monkey-playing skills, portraying the Monkey King’s breadth of vision as well as his resourcefulness, liveliness and adroitness. A few Peking Opera actors made their name by playing the Monkey King. They include Yang Yuelou (1844-1889) and Yang Xiaolou (1878-1938), who were father and son, Li Shaochun (1919-1975), Li  Wanchun (1911-1985) and Ye Shenzhang (1912-1966). During 1937-1942, Monkey King plays had their heyday in Beijing.

Wanchun (1911-1985) and Ye Shenzhang (1912-1966). During 1937-1942, Monkey King plays had their heyday in Beijing.

Often the Monkey King was staged in several theaters at the same time. Some theatrical companies even specialized in staging Monkey King plays, offering shows in series. In 1926, Peking Opera actors Yang Xiaolou and Zheng Faxiang staged Monkey King play in Japan. At the time, plays such as Havoc in Heaven (nao tian gong) and Water-curtained Cave (shui lian dong), both are episodes of Pilgrimage to the West featuring the Monkey King, were popular among foreign audiences.

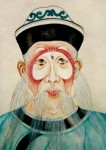

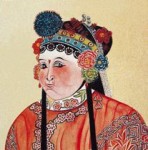

Intriguing Facial Makeup

Seeing a Peking Opera performance for the first time, a foreigner would wonder: why are faces of actors painted red, white, black, yellow or green? Are they masks? But masks are separate from the face. Facial makeups in Peking Opera are different from masks. Intrigued, many foreign tourists would go backstage to see actors and actresses remove stage makeup and costume. Next time, they would go there before a performance starts to see how performers do their makeup. Luciano Pararotti, the great tenor of international fame, once had a Peking Opera actor paint on his face the makeup of Xiang Yu, a valiant ancient warrior portrayed in numerous Peking Opera plays.

Seeing a Peking Opera performance for the first time, a foreigner would wonder: why are faces of actors painted red, white, black, yellow or green? Are they masks? But masks are separate from the face. Facial makeups in Peking Opera are different from masks. Intrigued, many foreign tourists would go backstage to see actors and actresses remove stage makeup and costume. Next time, they would go there before a performance starts to see how performers do their makeup. Luciano Pararotti, the great tenor of international fame, once had a Peking Opera actor paint on his face the makeup of Xiang Yu, a valiant ancient warrior portrayed in numerous Peking Opera plays.

The facial makeup is a unique way of portrayal in the traditional Chinese theater. Makeup types number thousands, and different types have different meanings. At an early date, most faces were painted black, red and white. As plays increase in number, opera artists used more colors and lines to paint the faces of characters, to either exaggerate or differentiate, according to Weng Ouhong, a researcher of the classic Chinese theater. They drew inspirations from classical novels, which portray characters as having “a face as red as a red jujube,” “a face the color of dark gold,” ”a ginger-yellow face,” “a green face with yellow beard,” “a leopard-shaped head with round eyes,” “a lion’s nose” or “broom-shaped eyebrows.” Seeing a Peking Opera performance for the first time, a foreigner would wonder: why are faces of actors painted red, white, black, yellow or green? Are they masks? But masks are separate from the face. Facial makeups in Peking Opera are different from masks. Intrigued, many foreign tourists would go backstage to see actors and actresses remove stage makeup and costume. Next time, they would go there before a  performance starts to see how performers do their makeup. Luciano Pararotti, the great tenor of international fame, once had a Peking Opera actor paint on his face the makeup of Xiang Yu, a valiant ancient warrior portrayed in numerous Peking Opera plays.

performance starts to see how performers do their makeup. Luciano Pararotti, the great tenor of international fame, once had a Peking Opera actor paint on his face the makeup of Xiang Yu, a valiant ancient warrior portrayed in numerous Peking Opera plays.

The facial makeup is a unique way of portrayal in the traditional Chinese theater. Makeup types number thousands, and different types have different meanings. At an early date, most faces were painted black, red and white. As plays increase in number, opera artists used more colors and lines to paint the faces of characters, to either exaggerate or differentiate, according to Weng Ouhong, a researcher of the classic Chinese theater. They drew inspirations from classical novels, which portray characters as having “a face as red as a red jujube,” “a face the color of dark gold,” ”a ginger- yellow face,” “a green face with yellow beard,” “a leopard-shaped head with round eyes,” “a lion’s nose” or “broom-shaped eyebrows.”

yellow face,” “a green face with yellow beard,” “a leopard-shaped head with round eyes,” “a lion’s nose” or “broom-shaped eyebrows.”

Color patterns painted on the faces of opera characters are called lianpu, or facial makeup. When a character’s face needs to be exaggerated, a makeup type is painted. The most common facial makeup types are jing and chou. Jing is an actor with a painted face and chou is the role of a clown. For different roles with different makeup types, ways of color application and painting are different. For some makeup types such as one for a hero, color is applied to the face with hand; no paintbrush is used. For most types of warrior, colors mixed with oil are painted on the face, and meticulous attention is paid to shades of coloring, the size of eye sockets and the shape of the eyebrows. For treacherous court officials, the face is painted white, with the eyebrows and eye corners slightly accentuated and a couple of “treachery” lines added.

A facial makeup type points to the personality of a particular character type. A red face indicates uprightness and loyalty, a black face a rough and forthright character, a blue face bravery and pride, a white face treachery and cunning, and a face with a white patch a fawning and base character. To show kinship, father and son can have faces of the same color with similar patterns. To show identity, a face with a dignified pattern belongs to a loyal official or a loving son, a blue-and-green face to an outlaw hero, a face with kidney-shaped eyes and wooden-club-shaped eyebrows to a monk, a face with sharp eye corners and a small mouth to a court eunuch, and a face with a white patch to a minor character.

Facial makeup can also allow actors to expand the scope of acting. If animals are to be portrayed, there is no need to have real horses and cattle on the stage. For example, in the play titled the Jinshan Temple, there is an army of shrimps and crabs fighting an evil character. They are played by performers with faces painted with a shrimp or crab. With novel patterns, bright colors, standard or wry contours and thick or thin lines, facial makeup can arouse the interest of the audience and add interest to Peking Opera performances.

Jing characters are also called “painted faces.” As the name suggests, they wear faces with complicated patterns, and different jing characters have different painted faces. But the clown, or chou, in Peking Opera was the earliest character to have a painted face. Compared with jing characters, clowns have a simple facial makeup, though it is not limited to a white patch on the face. Clowns usually make a greater impression on the audience than jing characters.

After years of development, there have been established rules on how to  paint faces and what different facial patterns represent. Types of facial makeup reveal the Chinese people’s evaluation of historical figures. For example, Cao Cao, a Han Dynasty prime minister, and Yan Song, a Ming Dynasty prime minister, wear a white face, indicating they are treacherous and cunning; Guan Yu, a general of the Three Kingdoms period, has a dignified red face, showing he was a loyal person; and Judge Bao wears a black face, meaning he was impartial and incorruptible as a judge.

paint faces and what different facial patterns represent. Types of facial makeup reveal the Chinese people’s evaluation of historical figures. For example, Cao Cao, a Han Dynasty prime minister, and Yan Song, a Ming Dynasty prime minister, wear a white face, indicating they are treacherous and cunning; Guan Yu, a general of the Three Kingdoms period, has a dignified red face, showing he was a loyal person; and Judge Bao wears a black face, meaning he was impartial and incorruptible as a judge.

Knowledge of facial makeup can help audiences understand the plot of Peking Opera. While facial makeup develops in operatic performance, masks have not been banished. In propitious and mythological plays, characters use masks called, for example, “god of wealth mask” and “god of thunder mask.” In some plays, facial makeup and masks appear on the stage at the same time.

For foreigners, the facial makeup in Peking Opera is quite mysterious. As a symbol of Peking Opera culture, facial patterns appear on an increasing  number of handicraft articles that hold a strong appeal to people. Even in fashion design, the Peking Opera makeup has become a chic factor shown on the T-shaped runway. Together with clothes, it has entered the life of people today.

number of handicraft articles that hold a strong appeal to people. Even in fashion design, the Peking Opera makeup has become a chic factor shown on the T-shaped runway. Together with clothes, it has entered the life of people today.

Peking Opera

Foreign visitors to China (especially in Beijing) usually first visit the Great Wall, the Forbidden City and the Temple of Heaven, representative sites of historical interest in the city. In the evening, a tourist guide will take foreign visitors to the Chang’an Grand Theater on the Avenue of Enduring Peace. In the foyer are counters selling handicraft articles, Peking Opera masks and Peking Opera-related books, picture albums and audio-video products.

Foreign visitors to China (especially in Beijing) usually first visit the Great Wall, the Forbidden City and the Temple of Heaven, representative sites of historical interest in the city. In the evening, a tourist guide will take foreign visitors to the Chang’an Grand Theater on the Avenue of Enduring Peace. In the foyer are counters selling handicraft articles, Peking Opera masks and Peking Opera-related books, picture albums and audio-video products.

Inside the theater, the stage is of a Western style; seats in the middle and rear rows are soft sofas; but in the front rows are exquisite Chinese-style square tables and armchairs. The traditional seats lend the theater a classical flavor.

Sitting in your seat, you might take a look at the Chinese fans around you. They all have a relaxed expression and wear ordinary clothes. Many of them are speaking in each other’s ears. But as soon as the gong and drum strike up, they all calm down and watch the play intently. As the plot unfolds, they seem to know who should be the next to come onto the stage and when to applaud a particular actor or actress for his or her performance.

More surprising, aside from applause, Chinese audiences show their appreciation for the performance of actors and actresses by shouting “hao!” It turns out that this means simply “well-done”or “bravo”.