Introduction of Ethnic Minority Styles

In as early as the Warring States Period, the sixth emperor of Zhao already  realized that although the Zhao army had better weapons, the long robes worn by generals and warriors were too cumbersome for an army, especially when they had to drag their armors and supplies around. They had tens of thousands of soldiers, but few riders flexible to make a quick attack. He went against all objections and advocated for change towards the Hu or western minority clothing style of the nomadic riders. The Zhao soldiers wore shorter robes and trousers and soon became a better army. Economic development followed.

realized that although the Zhao army had better weapons, the long robes worn by generals and warriors were too cumbersome for an army, especially when they had to drag their armors and supplies around. They had tens of thousands of soldiers, but few riders flexible to make a quick attack. He went against all objections and advocated for change towards the Hu or western minority clothing style of the nomadic riders. The Zhao soldiers wore shorter robes and trousers and soon became a better army. Economic development followed.

Moreover, this style that was once frowned upon and rejected became the daily wear of the common folks by Wei, Jin and Southern and Western Dynasties in the central plains. One reason for this change, unfortunately, was the frequent migration of the people to run away from the incessant wars and chaos. This process also helped the exchange of garment culture. Kuzhe and liangdang are the typical “Hu” or minority wear of that time. It is not hard to see that both styles are fit for riding and for life in the cold climate. The so-called kuzhe is a style with separate upper and lower garments. The upper garment looks like a short robe with wide sleeves, a central China adaptation to the original narrow sleeves fit for riding and herding animals. What also changed was the closure of the robe, which moved from left to right. Interestingly, people of central China called the northwestern people “people with left closure.” The robes at this time were shortened significantly, and varied in style. Historical materials show a number of styles of these upper garments in Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties, which had left, right and middle closure, or even swallowtails at the front hem. A set of these garments makes the wearer sharp and agile, as is frequently seen in clay burial figurines in the Southern Dynasty.

The lower garment of the kuzhe is a pair of trousers with closed crotch. Initially these trousers were close fitting, showing off slender legs that could freely move around. When this style appeared in central China, especially when some officials wore them in court, the conservatives questioned the appropriateness of the two thin legs that cried out rebellion against the loose fitting traditional ceremonial wear. Widening the legs was a compromise, so that the pants still appeared similar to the traditional robe. When walking about, these pants were more flexible and convenient than the robe. To avoid being caught in thorns or dragged in mud, someone came up with a brilliant idea of lifting the trouser legs and tying them up just below knee-level. This kind of pants can be frequently seen in the Southern Dynasty’s burial figurines and brick paintings. In appearance, they are quite similar to the bell bottomed pants in the modern days, but in reality, they are only similar in profile, not in construction.

Liangdang or double-layered suit is another style typical of this period, and it came from the northwest into central China. It was no more than a vest, which can be seen in many burial pieces of that time. Judging from clay figurines and wall paintings in tombs, the vest was in two separate pieces fastened on the shoulders and under the arms. There were also liangdangs worn inside in materials of leather or cotton, lined or unlined, close or loose fitting. The name has changed over the years but the style remained. The above mention garments were all the rage at that time for both women and men. The separate piece style has always been the prototype of the Chinese people, but modifications were made due to the exchange and fusion of different garment cultures.

Chinese Traditional Archery & Juyuanhao Workshop

The Ju Yuan Hao bow and arrow-making workshop used to be one of the 17 Imperial bow and arrow-making workshops in the gong jian da yuan (bow & arrow courtyard), located on Dongsi Street. This workshop is the only bow and arrow-making workshop that retains its bow and arrow-making tradition.

The Ju Yuan Hao bow is one kind of “recurve” Chinese traditional bow, which has a curvature when it is unstrung. Craftsmen first make a core for the bow from thin bamboo and attach the wooden grip and the ears. Then they firmly glue horn and sinew to the core. Finally craftsmen decorate the bow with material such as birch bark, symbols, and lacquer.

The traditional bow and arrow have struggled mightily in the market since the 1960s. In order to continue keep this technical tradition alive, the owner of the Ju Yuan Hao workshop, Yang Wentong, passed on his skills to his third son, Yang Fuxi.

Now, Mr. Yang Fuxi (Master of Ju Yuan Hao Workshop) is the only one who can make the Chinese traditional bow and arrows. Juyuanhao Workshop, today’s only one who can make Chinese traditional archery which were used by ancient Chinese Imperial Military. Features of Juyuanhao bow and arrows: Light,Durable,Immensely Accurate and Powerful.

In the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), bow makers were on the payroll of the Imperial Treasury and so, although their status was not high, they enjoyed extremely rich pickings and hence came to feel themselves several cuts above the rest of the ordinary people, living a life free of deprivation.

The Manchu banner men of those days often led pretty dissolute lives; the seventh generation of Ju Yuan Hao’s founder was no exception. Finally he became an opium addict and hardly had the willpower left to do any business. In the end, he had no choice but to sell off the family business.

Yang Wentong’s father Yang Ruilin was a craftsman who was infatuated with bow and arrow making when he knew the seventh-generation inheritor of the Ju Yuan Hao shop wanted to sell it, he immediately collected the money and bought it.

In the prosperous time, the “bow and arrow courtyard” could produce more than 500 bows a month. However, with the changes of time, Yang Wentong, the ninth-generation of Ju Yuan Hao makers, gradually went out the practice of making bows.

His fortune began to reverse itself in 1998, when Yang took his bows to an international archery competition. There, the coach of the national archery team took a fancy to his traditional bow, and from then on, Yang Wentong began to make bows again in his spare time, and also encouraged his sons to inherit the ancestral craft.

Alongside the development of science and technology, the traditional technique of bow and arrow making is facing permanent extinction.

Yang Fuxi, worried that the tradition could wither and die in his hands, so in order to pass on the technique, Yang Fuxi undertook the responsibility to save it.

When Yang Fuxi first learned how to make the bow and arrow, he was already 40 years old.

To master this craft, Yang Fuxi resigned from his work, and worked as a taxi driver for 4 years. During this time all the money he saved was used to purchase material. Starting from 1998, Yang Fuxi devoted himself to making the bow and arrow.

Bows and arrows are complex to make, demanding in their construction and particularly needing an accumulation of experience. There is no way to train someone in a few short years to undertake the whole process: At best people might get very skilled with one part of it.

In the first year, Yang Fuxi made 40 bows, but he only sold one. Yang Fuxi, the only continuator of Ju Yuan Hao.

Yang helplessly said that he eagerly hoped there was someone who could master the skill. There are many processes for making one bow. Even some original professionals have a mastery of only one or two working procedures.

Besides the complex procedures, traditional arrow manufacture needs many material, like silk, bamboo, horn, tendon, wood, rubber, lacquer, skin, and so on; these material are hard to obtain or even to find today.

Moreover, as a bow maker, one must know many other technologies, and must be able to sink his or her heart into learning this dirty, tiring job.

An ordinary bow can be sold for 100 Yuan, or about US$12.5, and a special-made strong one is worth one or two thousand Yuan. However,  compared with the time and energy spent on making it, such a price is not high. But today (from the year of 2009), the price of Juyuanhao bow is more than USD1000.00 (including 5 arrows). More information about Juyuanhao bow and aroows, please visit web at http://www.juyuanhao.org directly.

compared with the time and energy spent on making it, such a price is not high. But today (from the year of 2009), the price of Juyuanhao bow is more than USD1000.00 (including 5 arrows). More information about Juyuanhao bow and aroows, please visit web at http://www.juyuanhao.org directly.

Yang Fuxi said making a traditional bow was too hard. Generally, it would take him 3 to 4 months to make only 10 to 12 bows. This is because there are nearly 200 steps for making a single bow. For making a superior bow, the technique is more complicated.

It is Difficult to Find an Apprentice

Many traditional crafts like bow and arrow making are facing the prospect that once the old craftsmen pass away, the technique will be forever lost. Yang Fuxi said he want to have an apprentice, but so far he has been unable to find one. Bow making is hard work that cannot earn much money, so many young people do not want to learn it.

Not long before, Yang was offered a job as the folk researcher in the China Culture Academy. He told journalists that the reason that he and other handicraftsmen worked as researchers was to protect and pass on the folk technique. Yang said that soon, the government and research institute would record some words and audiovisual aids for them so that later generations could resume the crafts.

Reason for Optimism:

In the earliest Chinese royal dynasties, archery had an important place both in mystic ritual and in war. It was a compulsory subject, together with ritual, music, charioteering, reading, and arithmetic in the schools that trained the Chinese nobility.

At present, although archery is no longer a fighting skill used in the battlefield, it’s not merely a traditional sport. More important, much China traditional culture is contained in the archery. By study traditional archery, people can learn about some of China’s traditional lifestyle as well its traditional way of thinking, which might have some influence on today’s society.

Yang Fuxi said that Ju Yuan Hao has weathered the storms of three centuries, sometimes at the crest of the waves and sometimes in the troughs. He said people should have faith that in these days of China’s open economy, the Ju Yuan Hao can be rode up to a crest once again.

Juyuanhao videos from Discovery (Approximate 7 Minutes):

Chinese traditional archery which for ancient Chinese Imperial Military:

How to buy one Chinese traditional Bow (Juyuanhao Bow):

- Please click “Making Bow and Arrows” on the left column of www.juyuanhao.org ;

- Please click “Select your currency” on the left column of www.juyuanhao.org ;

- Follow the instructions of the website.

Three Masters Focusing on Temperament and Taste

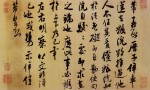

Part of Scroll of a Poem on the Miserable Life in Huangzhou, written in running script by Su Shi. This chapter will introduce three calligraphy masters from the Song Dynasty: Su Shi, Huang Tingjian and Mi Fu, not because they were active in the latter half of the 11th century, and not because they were friends, but because they developed spontaneously a style focusing on the expression of emotion and feelings. Now we introduce them in the order of their ages. Su Shi had extra talents and knowledge and was an outstanding man of letters, painter and calligrapher. His bold poems constitute his own unique school and were praised highly by the people of his age and the people of later generations. He had a good command of the running and regular scripts. But his political life was turbulent, and he was exiled from the capital several times. Once he was slandered and thrown in prison for 130 days. Saved by the empress dowager and key ministers, he survived but was exiled to Huangzhou in south China. One spring day in the third year of his life in Huangzhou, he wrote a poem to describe his misery. Then he turned the poem into the famous Scroll of a Poem on the Miserable Life in Huangzhou. This poem contains 120 characters in 24 sentences. Many changes in the strokes express a profound artistic conception which matches the depression expressed by the poetic lines.

At the beginning, the characters progress slowly, and show even spaces between them. He uses bent strokes, and oblique parts and lines to express his unquiet heart. In the second character on the second line the last vertical stroke is written like a sharp sword, occupying a large space, which exudes boundless feelings. What we see here is part of the work. The last sentence means that he wants to go back to the capital city, but there are nine gates to pass through, and he wants to go back to his hometown, but the tombs of his relatives are far away. With different sizes, these characters show strong contrasts, and demonstrate his unstable mind and resentment, and also his perplexity and pessimism. The shapes of the dots and strokes, their strength, speed, falsity and reality, density and looseness, and the ups and downs of their rhythm and changes show the natural harmony of the whole work.

Su Shi left behind him many poems and brief comments on calligraphy.  “Innocence and romanticism are my teachers, with imagination and creation, I finish my calligraphic works, free from traditional rules. I write dots and strokes freely, without any restrictions.” He once said that he enjoyed handwriting. It was better for old people to write than to play chess, he said. In the postscript written on a calligraphic work by a friend, he said that calligraphy was a game played with strokes. Su Shi loved painting too. The themes of his paintings are not concrete things, but the water, rocks and hills in his mind or the resentment in his heart. Huang Tingjian was a master of poetry and calligraphy. When he was an official he always had trouble, and was exiled from the capital several times. His calligraphic works are powerful and changeable. The characters in his regular and running scripts extend outward. His handwriting in the wild cursive script is better than that of his teachers. Scroll to Eminent Monks (see next page) expresses his unconstrained, straightforward and loquacious nature. Huang Tingjian emphasized gracefulness in his calligraphy. Like Su Shi, he took calligraphy as a game. Mi Fu was also good at poetry and calligraphy. He was brave and unyielding. His personality shows in his unrestrained, light and natural running and cursive script handwriting. His Collection of Tiaoxi Brook Poems in the running script is a good example of this.

“Innocence and romanticism are my teachers, with imagination and creation, I finish my calligraphic works, free from traditional rules. I write dots and strokes freely, without any restrictions.” He once said that he enjoyed handwriting. It was better for old people to write than to play chess, he said. In the postscript written on a calligraphic work by a friend, he said that calligraphy was a game played with strokes. Su Shi loved painting too. The themes of his paintings are not concrete things, but the water, rocks and hills in his mind or the resentment in his heart. Huang Tingjian was a master of poetry and calligraphy. When he was an official he always had trouble, and was exiled from the capital several times. His calligraphic works are powerful and changeable. The characters in his regular and running scripts extend outward. His handwriting in the wild cursive script is better than that of his teachers. Scroll to Eminent Monks (see next page) expresses his unconstrained, straightforward and loquacious nature. Huang Tingjian emphasized gracefulness in his calligraphy. Like Su Shi, he took calligraphy as a game. Mi Fu was also good at poetry and calligraphy. He was brave and unyielding. His personality shows in his unrestrained, light and natural running and cursive script handwriting. His Collection of Tiaoxi Brook Poems in the running script is a good example of this.

Mi Fu’s articles on calligraphy, like his calligraphic works, focus on graceful and romantic touches. By these standards, he assessed the calligraphic works of his predecessors. He even criticized Yan Zhenqing, a calligrapher of the mid-Tang Dynasty, who opened a new chapter for the development of calligraphy, saying that Yan’s regular script handwriting was too plain. Like Su Shi and Huang Tingjian, he believed that calligraphy was a game, saying, “Calligraphy is a game, so it is unnecessary to consider the characters as beautiful or ugly. It is enough if you are satisfied with your work. After you put down the brush, the game is over.”

These three calligraphy masters from the Song Dynasty were influenced by the prevailing cultural trends and aesthetic viewpoints. The Song Dynasty was influenced by the developed culture of the Tang Dynasty, but it met internal and external unrest. The men of letters had less aspirations and progressive enthusiasm than those of the Tang Dynasty. When they found it difficult to realize their high ambitions, they devoted themselves to poetry, calligraphy and other artistic activities exclusively. Opposite to the vigorous and forceful style of the Tang Dynasty, the poetry of the Song Dynasty sought a deep and cold resonance. Tang paintings have landscape, flowers, birds and natural scenes as the background, and beautiful women, cows and horses playing the main roles. But the landscape paintings of the Song Dynasty have natural scenes as the main objects.

Therefore, the people of the Song Dynasty liked the running-script calligraphy, a script between the regular and the cursive scripts – not rigorous like the regular script, and easier to learn and recognize than the cursive script. The running script is convenient for the calligrapher to use his brush, and makes it easy for him to express his peaceful, simple and leisurely mind, and to realize his aspiration to be happy through calligraphy.

The sentiments and interests the Song calligraphers sought are similar to but different from the gracefulness cherished by the Jin calligraphers. Both emphasized the beauty of the image of the objects and the beauty of the interest and charm of calligraphy. But the gracefulness cherished by the Jin masters has a narrow connotation, merely having a peaceful, plain and quiet tone. While playing such an artistic game, the Song calligraphers got rid of all  kinds of shackles and pressures, and created works in a powerful and unconstrained style. They reached the best understanding of the poetry and handwriting, and expressed them in the best way. So the calligraphers took their counterparts from the Jin Dynasty as their teachers but they outstripped their counterparts in purport and techniques. This is obvious from a comparison of the handwriting in the running and cursive scripts by the Song calligraphers with those of the Jin calligraphers.

kinds of shackles and pressures, and created works in a powerful and unconstrained style. They reached the best understanding of the poetry and handwriting, and expressed them in the best way. So the calligraphers took their counterparts from the Jin Dynasty as their teachers but they outstripped their counterparts in purport and techniques. This is obvious from a comparison of the handwriting in the running and cursive scripts by the Song calligraphers with those of the Jin calligraphers.

Two Masters of the Tang Dynasty

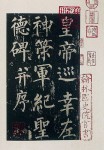

Buy Cialis Super Active+ Online alt=”Jiucheng Palace Tablet,writtern in regular script by Ouyang Xun” width=”69″ height=”122″ />this chapter, we will introduce Chu Suiliang and Yan Zhenqing, the two leaders of the trend in calligraphy trend at that time. In the early years of the Tang Dynasty, there were four famous calligraphers: Ouyang Xun, Yu Shinan, Chu Suiliang and Xue Ji, in order of their ages.

Buy Cialis Super Active+ Online alt=”Jiucheng Palace Tablet,writtern in regular script by Ouyang Xun” width=”69″ height=”122″ />this chapter, we will introduce Chu Suiliang and Yan Zhenqing, the two leaders of the trend in calligraphy trend at that time. In the early years of the Tang Dynasty, there were four famous calligraphers: Ouyang Xun, Yu Shinan, Chu Suiliang and Xue Ji, in order of their ages.

Chu Suiliang (596-658) was once an official of the imperial court, and wrote the draft declaration made by Emperor Taizong when he abdicated in favor of his son. When the new emperor, Gaozong, married Wu Zetian, one of his father’s concubines, Chu protested, and was exiled from the capital.

Preface to Tripitaka, written in regular script by Chu Suiliang. Chu studied the calligraphic styles of Ouyang Xun and Wang Xizhi, and the Han official script. He combined all these into a new type of script, abandoning the”silkworm’s head” and “wild goose’s tail.” His calligraphic style underwent three major changes. The Preface to Tripitake is one of his masterpieces. Written in the regular script, the characters are thin and smooth, but powerful. It became fashionable to copy his handwriting, and he himself was praised as a calligraphy master of the Tang Dynasty.

Yan Zhenqing (708-784) was born into an aristocratic family. His grandfather and paternal uncle were calligraphers, and instilled a love of calligraphy into him. Yan passed the highest imperial examination and became an official for a time. His powerful and vigorous handwriting in the regular or running scripts reflect his lofty moral character.

At first, Yan copied Chu’s style, and later Wang Xizhi’s. He finally developed a powerful, fantastic and beautiful style, which was in harmony with the flourishing culture of the powerful Tang Dynasty. His style has been enthusiastically followed by later generations.

Here we should introduce Liu Gongquan (778-865) who was born 70 years later, and became as famous as Yan, whose style he studied.

Liu Gongquan received encouragement from several emperors, who were his patrons. Liu’s characters are powerful, vigorous and smooth, and the strokes extend outward. He is famous for his command of tension and the cohesion of his ink. Like Yan’s, Liu’s calligraphy has been copied widely by people of later generations.

patrons. Liu’s characters are powerful, vigorous and smooth, and the strokes extend outward. He is famous for his command of tension and the cohesion of his ink. Like Yan’s, Liu’s calligraphy has been copied widely by people of later generations.

Rigor is the most important characteristic of the calligraphers of the Tang Dynasty. The Tang style is quite different from that of the Jin Dynasty, which is elegant, graceful, unrestrained and beautiful, while that of the Tang Dynasty is strict and neat, and easy to learn. From the Tang Dynasty on, calligraphy became an art involving many more people.