Father and son: Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi

us know several key creation trends in the development of Chinese calligraphy in the Jin, Tang, Song and Qing dynasties. Leading these creation trends were calligraphic masters of their periods.

us know several key creation trends in the development of Chinese calligraphy in the Jin, Tang, Song and Qing dynasties. Leading these creation trends were calligraphic masters of their periods.

This chapter deals with a father and a son of the Jin Dynasty – Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi. The former was praised as a sage in calligraphy circles. Wang Xizhi was born into a noble family. His grandfather, father and two brothers were senior officials of the imperial court. His family was a calligraphic family too. Historical records show that of the nearly 100 famous calligraphers of the Jin Dynasty, 20 were of the Wang clan. In his youth, Wang Xizhi was once a petty official, who gave up official life to live as a hermit and devote himself to calligraphy. He is said to have created nearly 1,000 calligraphic works, but none of the originals have survived. Those we can see today are copies made by calligraphers of later periods. Of these dozen or so copies, most are in the running and regular scripts, and only one is in the cursive script.

wp-att-882″ href=”http://www.chinascan.org/archives/874/two-notes-of-running-script-by-xie-an”> Wang Xizhi learnt calligraphy from his father first, and then from the famous woman calligrapher Madam Wei. In middle age, he crossed the Yangtze River to visit many famous mountains in north China, met many famous calligraphers and examined a lot of stele inscriptions. He studied calligraphic theory and developed a natural and unrestrained new style. For a time, this new style was adopted by the sons and nephews of the famous contemporary calligrapher Yu Yi, much to the latter’s chagrin. But before long ,Yu Yi himself admired Wang’s new style for its vividness and shiningness.

Wang Xizhi learnt calligraphy from his father first, and then from the famous woman calligrapher Madam Wei. In middle age, he crossed the Yangtze River to visit many famous mountains in north China, met many famous calligraphers and examined a lot of stele inscriptions. He studied calligraphic theory and developed a natural and unrestrained new style. For a time, this new style was adopted by the sons and nephews of the famous contemporary calligrapher Yu Yi, much to the latter’s chagrin. But before long ,Yu Yi himself admired Wang’s new style for its vividness and shiningness.

Wang’s new style was a milestone in the history of Chinese calligraphy,  praised as a pleasing departure from the old styles of Zhong You and Zhang Zhi of the Eastern Han Dynasty.

praised as a pleasing departure from the old styles of Zhong You and Zhang Zhi of the Eastern Han Dynasty.

Xie An, a grand councilor of the Jin Dynasty, was one of the 41 man of letters who gathered at the Orchid Pavilion (see p. 5). He learnt the cursive script from Wang. Wang Xianzhi was once an official of the imperial court, of higher rank than his father. Like his father, he was a man of integrity. When Xie An asked him to write Part of an inscription for a new hall, he refused, because he thought the elegant hall had been built against the will of the people. A legend has it that in his teens, he told his father that the “zhang cao” cursive script was too restricted, and proposed developing a new style midway between the cursive and running scripts. Later, Wang Xianzhi developed the unique running-cursive script. His Short Note of Duck-Head Pill in the running script (see next page) contains 15 characters in two lines. All the characters are natural and smooth, unrestrained and lyrical. In this, he surpassed his father.

According to Sun Guoting’s Treatise on Calligraphy, one day, Xie An asked Wang Xianzhi, “In comparison with your father’s handwriting, what do you think of your own?” Wang answered, “Certainly, my handwriting is better than my father’s.” “But the critics do not think so,” said Xie An. “They do not understand,” said Wang Xianzhi. Sun Guoting criticized Wang for this. But this short note shows that his handwriting is in fact better than his father’s. In his On Calligraphy, Zhang Huaiguan of the Tang Dynasty said that Wang Xianzhi possessed exceptional talent, and developed a new style different from both the running and cursive scripts. This new style was unrestrained, and became very fashionable.

The Jin Dynasty was racked by internal disturbances and foreign invasions, and many talented people forsook politics for intellectual and philosophical pursuits. Scholars sought to explore life and demanded the liberation of the personality in a revival of the “hundred schools of thought.”

The Jin Dynasty was racked by internal disturbances and foreign invasions, and many talented people forsook politics for intellectual and philosophical pursuits. Scholars sought to explore life and demanded the liberation of the personality in a revival of the “hundred schools of thought.”

Following this trend, literature and art got rid of the shackles of Confucian doctrine step by step, and sought ways to express emotions and feelings with charm and vigor. Calligraphy, the most concentrated expression of the aesthetic viewpoint of the Jin Dynasty, emphasized the expression of inner emotions and feelings through the patterns of dots and strokes. Calligraphers vied each other to update their handwriting techniques, patterns of characters and structures, thus pushing calligraphic art to its first historical peak.

Shaanxi History Museum

The Shaanxi History Museum is situated on Yan Ta Road in Xi’an City, Shaanxi Province. It covers 65,000 square meters, with a building area of 60,000 square meters. The newly built modern building recreates Tang-dynasty architecture and successfully symbolizes the great extent of Shaanxi history and its remarkable culture.

The Shaanxi History Museum is situated on Yan Ta Road in Xi’an City, Shaanxi Province. It covers 65,000 square meters, with a building area of 60,000 square meters. The newly built modern building recreates Tang-dynasty architecture and successfully symbolizes the great extent of Shaanxi history and its remarkable culture.

Exhibited in the main exhibition hall are 2,700 works of art, with an  exhibition line that extends 2,300 meters. The exhibition space is divided into an introductory hall, permanent exhibitions, special exhibitions, and temporary exhibitions, as well as one that has been named the National Painting Hall.

exhibition line that extends 2,300 meters. The exhibition space is divided into an introductory hall, permanent exhibitions, special exhibitions, and temporary exhibitions, as well as one that has been named the National Painting Hall.

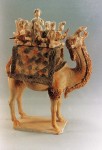

The Museum’s permanent exhibition primarily displays Shaanxi’s ancient history. Representative pieces from all periods have been selected to show the development of civilization in this region. The exhibition space of this display is 4,600 square meters. It includes three exhibition rooms, divided into seven parts (Prehistory, Zhou, Qin, Han, Wei-Jin-North and South dynasties, Sui-Tang, and Song-Yuan-Ming-Qing). The superlative 2,000 selected objects include: painted Neolithic ceramics reflecting early people’s living conditions and their pursuit of vibrant art forms, bronzes reflecting the rise of Zhou people, bronze weapons including swords, and statuary of horses and soldiers, reflecting the way in which Qin unified all under heaven, Tang-dynasty gold and silver objects and Tang sancai (tri-colored pottery of Tang dynasty) ceramics, reflecting the most flourishing period of feudal glory. All of this is accompanied by models of archaeological sites, and drawings, and photographs. These works systematically exhibit the ancient history of Shaanxi from 150,000 years ago to the year 1840. Since several historical periods all based their capitals on Shaanxi territory, such as Zhou, Qin, Western Han, Sui and Tang, the exhibits emphasize these periods and these places. This not only expresses the extent of culture in ancient Shaanxi, it also displays the highest level of cultural development of China’s social economy.

The temporary exhibits hall, located on the east side of the museum, has had a variety of exhibitions including Tang-tomb wall paintings, that is to say 39 of the actual paintings. Shaanxi’s wall murals of this kind rank first in the entire country. They are fluid in concept and line, they have marvelous details, and they both depict Tang customs and are superb works of art.

The temporary exhibits hall, located on the east side of the museum, has had a variety of exhibitions including Tang-tomb wall paintings, that is to say 39 of the actual paintings. Shaanxi’s wall murals of this kind rank first in the entire country. They are fluid in concept and line, they have marvelous details, and they both depict Tang customs and are superb works of art.

The special exhibition hall is located on the west side of the museum. Its first two exhibitions were a Shaanxi bronzes exhibit (260 were on display) and a Shaanxi-through-the-dynasties terracotta masterpieces exhibit (341 objects were exhibited). The area of this hall is around 2,600 square meters.

The Shaanxi History Museum contains 115,000 objects in its collections. The more representative of these include bronzes, Tang-dynasty tomb wall paintings, terracotta statuary, ceramics (pottery and porcelain), construction materials through the dynasties, Han and Tang bronze mirrors, and coins and currency, calligraphy, rubbings, scrolls, woven articles, bone articles, wooden and lacquer and iron and stone objects, seals, as well as  some contemporary cultural relics and ethnic objects.

some contemporary cultural relics and ethnic objects.

Address: Shaanxi Province, Xi’an City, Yanta Road, #70

Shanghai Museum

The scope, depth and quality of its collections, and the striking architecture and use of modern technology make the Shanghai Museum one of the most famous if not the most famous in China. It covers an area of 38,000 square meters, with a scale that surpasses the old museum several fold. The exterior of the museum utilizes the shape of an ancient bronze ding, specifically a Chen ding, with its rather archaic flavor. The structure and materials of the entire building, however, are an accomplishment of the most modern technology.

The scope, depth and quality of its collections, and the striking architecture and use of modern technology make the Shanghai Museum one of the most famous if not the most famous in China. It covers an area of 38,000 square meters, with a scale that surpasses the old museum several fold. The exterior of the museum utilizes the shape of an ancient bronze ding, specifically a Chen ding, with its rather archaic flavor. The structure and materials of the entire building, however, are an accomplishment of the most modern technology.

The Shanghai Museum is mainly a museum for ancient arts. At present it is divided into ten sections. These are: ancient Chinese bronzes, sculpture, ceramics, jades, seals, calligraphy, coin and currency, paintings, Ming and Qing-dynasty furniture, and crafts of China’s national minorities. In addition to these ten permanent exhibitions, the museum often holds small-scale exhibitions and also exhibits articles from elsewhere on a short-term basis. The Museum also exhibits its material in museums both within China and abroad.

Among the holdings of the Museum many items are superlative works of art and are unique in the entire country. These include in particular the bronzes, calligraphy, paintings, and Ming and Qing furniture.

China’s Shang and Zhou-period bronzes are an important testimony to the ancient civilization of the country. When visitors enter the Ancient Bronzes Hall, the presentation and atmosphere of the rooms expresses the cultural atmosphere of the Bronze Age. The subdued dark-green tone of the walls imparts an ancient atmosphere, the simple and elegant display cases and the lighting are carefully designed to enhance the experience. Some 400 exquisite bronze items are displayed in a space of 1,200 square meters, perfectly reflecting the history of the development of China’s ancient bronze arts.

The Calligraphy Hall includes works from many dynasties; in chronological order it displays the history of the marvelous genius of Chinese calligraphic arts. The aura of the hall is scholarly and elegant, assisted by automatic lighting in display cases that protects the art by shining only when the visitor is viewing a work. Among these works are a number of unique world treasures.

The Chinese Painting Hall of the Museum similarly has a touch of traditional architectural style to it, combined with an atmosphere of Confucian elegance. Around 120 masterpieces are displayed in the 1,200-square-meter exhibition space. These date from the Tang dynasty to modern times but do not include contemporary works.

The apex of Chinese furniture creation occurred during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Walking into the Ming and Qing Furniture Hall is like walking back into the gardens and rooms of the Ming and Qing dynasty. In some 700 square meters of space are exhibited some 100 pieces of superlative Chinese Ming and Qing-dynasty furniture. Among these are Ming pieces that are fluid in line and harmonious in proportion. The Qing pieces have more complex ornamentation and are often made of thicker, heavier wood.

The underground part of the Shanghai Museum also has some courtyard gardens that imitate authentic Chinese traditions. Although these are hidden deeply underground, their architecture and environment seem light and airy.

The underground part of the Shanghai Museum also has some courtyard gardens that imitate authentic Chinese traditions. Although these are hidden deeply underground, their architecture and environment seem light and airy.

Address: Shanghai, Peoples Great Road, #201

View of Chinese Bronze Ware

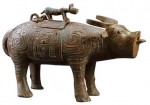

Bronze is the earliest of all alloys produced by the human race. In China, the earliest bronze ware were produced in the late period of the primitive society, and those produced during the Shang-Zhou period, in large quantities with the production techniques rated as better than ever before, highlight the social estate system practiced at the time. Bronze ware used before the Qin-Han period fall into three categories – those used at sacrificial ceremonies held by the state and aristocratic families, those for daily use by aristocrats and those used as funerary objects. Bronze articles for practical use include weapons, musical instruments, cooking utensils, and food, wine and water containers, as well as ornamental articles on horse chariots.

Bronze is the earliest of all alloys produced by the human race. In China, the earliest bronze ware were produced in the late period of the primitive society, and those produced during the Shang-Zhou period, in large quantities with the production techniques rated as better than ever before, highlight the social estate system practiced at the time. Bronze ware used before the Qin-Han period fall into three categories – those used at sacrificial ceremonies held by the state and aristocratic families, those for daily use by aristocrats and those used as funerary objects. Bronze articles for practical use include weapons, musical instruments, cooking utensils, and food, wine and water containers, as well as ornamental articles on horse chariots.

Bronze weapons unearthed so far are mostly swords, axes, axe-spears and dagger-axes. Bells in complete sets known as  bianzhong and large bells known as bo are the most typical bronze musical instruments played at sacrificial ceremonies and on other important occasions. Tripods and quadripods with hollow legs (li), which originated from prehistory cooking utensils, were used to boil whole animal carcasses for sacrificial ceremonies and feasting. Rules based on the social estate system were strictly followed with regard to the use of bronze ware. Nine tripods and eight food containers known as gui were allowed on occasions presided over by the “Son of of Heaven in rank may use seven tripods and six guis or five tripods and four guis. In short, the number of bronze containers decreased progressively according to the degrading ranks of the users. There were also stringent rules on the size and weight of the utensils for users of each rank. Wine sets are in greater variety than any other kind of bronze ware we have found so far – possibly because people of the Shang-Zhou period were fond of drinking wine. The earliest bronze wine sets include jue (wine vessel with three legs and a loop handle), jia (round-mouthed wine vessel with three legs) and hu (squaremouthed wine containers). Many wine containers take the shape of birds or animals.

bianzhong and large bells known as bo are the most typical bronze musical instruments played at sacrificial ceremonies and on other important occasions. Tripods and quadripods with hollow legs (li), which originated from prehistory cooking utensils, were used to boil whole animal carcasses for sacrificial ceremonies and feasting. Rules based on the social estate system were strictly followed with regard to the use of bronze ware. Nine tripods and eight food containers known as gui were allowed on occasions presided over by the “Son of of Heaven in rank may use seven tripods and six guis or five tripods and four guis. In short, the number of bronze containers decreased progressively according to the degrading ranks of the users. There were also stringent rules on the size and weight of the utensils for users of each rank. Wine sets are in greater variety than any other kind of bronze ware we have found so far – possibly because people of the Shang-Zhou period were fond of drinking wine. The earliest bronze wine sets include jue (wine vessel with three legs and a loop handle), jia (round-mouthed wine vessel with three legs) and hu (squaremouthed wine containers). Many wine containers take the shape of birds or animals.