Origin of Portery Art

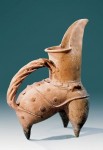

For people in the earliest stage of human development, it is earth on which they lived that gave them the earliest artistic inspiration. That may explains how the earliest pottery was made. The process seems pretty simple: mixing earth with water, shaping the mud by pressing and rubbing with hands and fingers until the roughcast of something useful was produced, placing the roughcast under a tree for air drying and then baking it in fire until it becomes hardened.

For people in the earliest stage of human development, it is earth on which they lived that gave them the earliest artistic inspiration. That may explains how the earliest pottery was made. The process seems pretty simple: mixing earth with water, shaping the mud by pressing and rubbing with hands and fingers until the roughcast of something useful was produced, placing the roughcast under a tree for air drying and then baking it in fire until it becomes hardened.

Before they began producing clay ware, prehistory people had, for many, many millenniums, limited themselves to changing the shapes of things in nature to make them into production tools or personal ornaments. For example, they crushed rocks into sharp pieces for use as tools or weapons, and produced necklaces by stringing animal teeth or oyster shells with holes they had drilled through. Pottery making, however, was revolutionary in that it was the very first thing done by the human race to transform one thing into another, representing the beginning of human effort to change Nature according to Man’s own design and conception. Prehistory pottery vessels are crude in shape, and the color is inconsistent because their producers were yet to learn how to control the temperature of fire to ensure quality of what they intended to produce. Despite th at, prehistory pottery represents a breakthrough in human development.

Regretfully, scholars differ on exactly how and when pottery – making began. According to a most popular assumption, however, prehistory people may have been inspired after they found, by accident, that mud-coated baskets placed beside a fire often became pervious to water.

View of China’s Cultural Relics

The Chinese civilization is one of the four most ancient in the world. Relative to the Egyptian, Indian and Tigris-Euphrates civilizations, it is characterized by a consistency and continuity throughout the milleniums. Rooted deep in this unique civilization originating from the Yangtze and Yellow River valleys, a yellow race known as the “Chinese” has, generation after generation, stuck to a unique cultural tradition. This tradition has remained basically unchanged even though political power has changed hands numerous times. Alien ethnic groups invaded the country’s heartland numerous times, but in the end all of them became members of a united family called “China”.

Cultural relics, immeasurably large in quantity and diverse in variety and artistic style, bespeak the richness and profoundness of the Chinese civilization. These, as a matter of fact, cover all areas of the human race’s tangible culture. This book classifies China’s cultural relics into two major categories, immovable relics and removable relics.”Immovable relics” refer to those found on the ground and beneath, including ancient ruins, buildings, tombs and grotto temples. “Removable relics” include stone, pottery, jade and bronze artifacts, stone carvings, pottery figurines, Buddhist statues, gold an silver articles, porcelain ware, lacquer works, bamboo and wooden articles, furniture, paintings and calligraphic works, as well as works of classic literature. This book is devoted to removable cultural relics, though from time to time it touches on those of the first category.

Far back in the 11th century, when China was under the reign of the North Song Dynasty, scholars, many of whom doubled as officials, were already studying scripts and texts inscribed on ancient bronze vessels and stone tablets. As time went by, an independent academic discipline came into being in the country, which takes all cultural relics as subjects for study. New China boasts numerous archeological wonders thanks to field studies and excavations that have never come to a halt ever since it was born in 1949. This is true especially to the most recent two decades of an unprecedented construction boom in China under the state policy of reform and opening to the outside world, in the course of which numerous cultural treasures have been brought to daylight from beneath the ground?

Readers may count on this book for a brief account of China’s cultural relics of 12 kinds – pottery, jade artifacts, bronze ware, figurines, carvings on stone tablets, murals, grottoes and formative art of Buddhism, gold and silver artifacts, porcelain, furniture, lacquer works, and arts and handicrafts articles. We’ll concentrate, however, on the most representative, most brilliant works of each kind while briefing you on their origin and development.

Unfortunately, we can not show you all kinds of cultural relics unique to China, for example those related to ancient Chinese mintage,printing and Chinese classics, traditional Chinese paintings and calligraphy. To cite an old Chinese saying, what we have done is just “a single drop of water in an ocean.” Despite that, we hope you’ll like this websit, from which we believe you’ll gain some knowledge of the traditional Chinese culture.

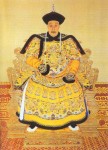

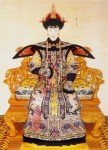

Royal Ceremonial Wear

The mianfu and the dragon robe are typical garments for ancient Chinese emperors. They serve as a micro cosmos that exemplify the unique Chinese aesthetic and sense of the universe.

The mianfu and the dragon robe are typical garments for ancient Chinese emperors. They serve as a micro cosmos that exemplify the unique Chinese aesthetic and sense of the universe.

In Chinese history there is a story of “Dressed with yellow robe” that occurred in 959 A.D. One year after a young emperor took over the throne at the death of his father, the old emperor, a general was dressed with the royal yellow robe by his supporters and made emperor. That was the beginning of the Song Dynasty. But why does the “yellow robe” represent the emperor? It all started in the Han Dynasty.

The Chinese theories of the Yin and Yang and of the Five Elements all try to explain the interdependence and mutual rejection of gold, wood, water, fire and earth. White represents gold; green represents wood; black represents water; and yellow represents earth. In Zhou Dynasty, red was regarded as the superior color for garments, but by Qin Dynasty (221 B.C.-206 B.C.) black ranked highest among all garment colors. All officials followed suit and wore black as much as they could. When Han Dynasty replaced Qin, yellow was promoted to the highest place, favored by the emperors of the time. By Tang Dynasty the court made it official that no one, except the emperor, had the  right to wear yellow. This rule was passed all the way down to the Qing Dynasty. It was said that when the 11-year old Pu Yi (1906-1967), the last emperor, saw his 8-year old cousin wearing yellow silk as his clothes lining, he grabbed the sleeve and said: “How dare you use yellow!” The status of the color yellow was apparently supreme in their heart.

right to wear yellow. This rule was passed all the way down to the Qing Dynasty. It was said that when the 11-year old Pu Yi (1906-1967), the last emperor, saw his 8-year old cousin wearing yellow silk as his clothes lining, he grabbed the sleeve and said: “How dare you use yellow!” The status of the color yellow was apparently supreme in their heart.

In ancient Chinese society, it was all strictly specified which class should wear what on what occasions. What the emperor wore on important occasions had a special name: mianfu.

Mianfu is a set of garments including the mianguan, a crown with a board that leans forward, as if the emperor is bowing to his subjects in full respect and concern. Chains of beads hang at front and back normally twelve chains each, but also in numbers of nine, seven, five or three, depending on the importance of the occasion and the difference in ranks. The jade beads are threaded with silk, ranging from nine to twelve in number. Hairpins are used to fasten the crown to the hair, and two small beads hang above the ears of the wearer, reminding him to listen with discretion. This, like the board in front of the crown, has important political significance.

The upper garment of emperors is normally black while the lower garment is normally crimson. They symbolize the order of heaven and earth and should never be confused. Dragon is the dominant pattern embroidered on the emperors clothing, although another 12 kinds of decoration can be seen as well, including symbolic animals, or natural scenes with sun and moon. These pa????erns are allowed on the lords as well, but they differ in complexity according to different ranks and importance of the occasion.

Mianfu with upper and lower garments are fastened with a belt, under which a decorative piece called bixi or knee covering hangs down. This piece of decorative cloth originated in the days when people were wearing animal skins, used primarily for covering the abdomen and the genitals. This part of clothing remained until later years, becoming an important component of the ceremonial wear. Even later, the bixi became the protector of the royal dignity. The emperor’s bixi is pure red in color.

Shoes to go with the mianfu are made of silk with double-layered wooden soles. Another kind exists that uses flax or animal skin as the sole depending on the season. By order of importance, the emperor wore red, white or black shoes on different occasions.

The most outstanding feature of the Chinese royal attire is the

The most outstanding feature of the Chinese royal attire is the  embroidered dragon. In Ming and Qing Dynasties, the robe had to have nine dragons embroidered, on front and back of the two shoulders and two sleeves, as well as inside the front lapel, displaying the royal prominence bestowed by the gods.

embroidered dragon. In Ming and Qing Dynasties, the robe had to have nine dragons embroidered, on front and back of the two shoulders and two sleeves, as well as inside the front lapel, displaying the royal prominence bestowed by the gods.

Shenyi and Broad Sleeves

![]() The ancient Chinese attached great importance to the upper and lower garments on important ceremonial occasions, believing in its symbolism of the greater order of heaven and earth. At the mean time, one piece style co-existed starting from the shenyi of the Warring States Period, and developed into the Han Dynasty robe, the large sleeved changshan of the Wei and Jin Period, down to the “qi pao” of the contemporary times, all in the form of a long robe in one piece. Therefore, Chinese garments took the above-mentioned two basic forms.

The ancient Chinese attached great importance to the upper and lower garments on important ceremonial occasions, believing in its symbolism of the greater order of heaven and earth. At the mean time, one piece style co-existed starting from the shenyi of the Warring States Period, and developed into the Han Dynasty robe, the large sleeved changshan of the Wei and Jin Period, down to the “qi pao” of the contemporary times, all in the form of a long robe in one piece. Therefore, Chinese garments took the above-mentioned two basic forms.

Shenyi, or deep garment, literally means wrapping the body deep within the clothes. This style is deeply rooted in the traditional mainstream Chinese ethics and morals that forbid the close contact of the male and the female. At that time, even husband and wife were not allowed to share the same bathroom, the same suitcase, or even the same clothing lines. A married woman returning to her mother ’s home was not permitted to eat at the same table with her brothers. When going out, a woman had to keep herself fully covered. These rules and rituals were recorded in great detail in the Confucian Book of Rites.

The shenyi is made up of the upper and lower garment, tailored and made in a unique way. There is a special chapter in the Book of Rites detailing the make of the shenyi. It said that in the Warring States Period, the style of the shenyi must conform to the rites and rituals, its style fit for the rules with the proper square and round shapes and the perfect balance. It has to be long enough not to expose the skin, but short enough not to drag on the floor. The forepart is elongated into a large triangle, with the part above the waist in straight cut and the part below the waist bias cut, for ease of movement. The underarm section is made for flexible movement of the elbow, therefore the generous length of sleeves reaches the elbow when folded from the fingertips. Moderately formal, the shenyi is fit for both men of letters and warriors. It ranks second in ceremonial wear, functional, not wasteful and simple in style. Shenyi of this period can be seen in silk paintings unearthed from ancient tombs, as well as on clay and wooden figurines found in the same period, with clear indications of the style, and often even the patterns.

Material used for making shenyi is mostly linen, except black silk is employed in garments for sacrificial ceremonies. Sometimes a colorful decorative band is added to the edges, or even embellished with embroidered or painted patterns. When shenyi is put on, the elongated triangular hem is rolled to the right and then tied right below the waist with a silk ribbon. This ribbon was called dadai or shendai, on which a decorative piece is atached. Later on leather belt appeared in the garment of the central regions as an influence of nomadic tribes. A belt buckle is normally attached to the leather belt for fastening. Belt buckles are often intricately made, becoming an emerging craft at the Warring States Period. Large belt buckles can be as long as 30 centimeters, whereas the short ones are about 3 centimeters in length. Materials can be stone, bone, wood, gold, jade, copper or iron, with the extravagant ones decorated with gold and silver, carved in patterns or embellished with jade or glass beads.

Material used for making shenyi is mostly linen, except black silk is employed in garments for sacrificial ceremonies. Sometimes a colorful decorative band is added to the edges, or even embellished with embroidered or painted patterns. When shenyi is put on, the elongated triangular hem is rolled to the right and then tied right below the waist with a silk ribbon. This ribbon was called dadai or shendai, on which a decorative piece is atached. Later on leather belt appeared in the garment of the central regions as an influence of nomadic tribes. A belt buckle is normally attached to the leather belt for fastening. Belt buckles are often intricately made, becoming an emerging craft at the Warring States Period. Large belt buckles can be as long as 30 centimeters, whereas the short ones are about 3 centimeters in length. Materials can be stone, bone, wood, gold, jade, copper or iron, with the extravagant ones decorated with gold and silver, carved in patterns or embellished with jade or glass beads.

By Han Dynasty, shenyi evolved into what is called the qujupao or curved gown, a long robe with triangular front piece and rounded under hem. At the mean time, the straight gown or Zh?upao was also popular, and it was also called chan or yu. When straight gown first appeared, it was not allowed as ceremonial wear, for wearing out of the house or even for receiving guests at home. In Historical Records, comments are found on the disrespectful nature of wearing Chan and Yu to court. The taboo may have come from the fact that, before Han Dynasty, people in the central plains wore trousers without crotches, only two legs of the trousers that meet at the waist, similar to the Chinese infant pants. For this reason, the wearer may look disgraceful if the outer garment is not properly wrapped to cover the body. When dressing etiquette is discussed in Confucian classics, the outer garment is said not to be lifted even in the hottest days, and the only occasion allowing for lifting the outer garment is when crossing of the river. People of the central plains had to kneel before they sit. There were written rules on not allowing sitting with the two legs forward. This rule has to do with the clothing style of the time, when sitting in the forbidden posture may result in disgrace. Later on, along with the close interaction with the riding nomadic, people of the central plains started to accept trousers with crotches.

Historical evidence, be it Han tomb paintings, painted rocks or bricks, or clay and wooden figurines, all portray people wearing long gowns. This style is found most commonly in men, but sometimes in women as well. The so-called paofu refers to long robes with the following features. First of all, it has a lining. Depending on whether it is padded, the garment can be called jiapao or mianpao. Secondly, it most often comes with generously wide sleeves with cinched wrist. Thirdly, it has low cut cross collars to show the under garment. And fourthly, there is often an embroidered dark band at the collar, the wrists and the front hem, often in Kui (a Chinese mythical animal) or checker patterns. The paofu differ in length. Some robes can reach down to the ankles, often worn by men of letters or the elderly, while others are only long enough to cover the knees, worn mostly by warriors or heavy laborers.

Even after paofu became the mainstream attire, shenyi did not disappear – it remained as in women’s garments. First the front lapel elongated and developed into a shenyi with wrap-around lapel. As can be seen in the silk painting in the Changsha Mawangdui Tomb of Han Dynasty, the lady in the painting is dressed in a shenyi with wrap-around lapel, fully embroidered with dragon and phoenix and already a high achievement in the development of female garments.