Hua Mulan-a Chinese Heroine

A historical figure who is famous for disguising herself as a man is Hua Mulan. Her name has long been synonymous with the word “heroine”, yet opinions differ as to whether this is her real name. According to Annals of the Ming, her surname is Zhu, while the Annals of the Qing say it is Wei. Xu Wei offers yet another alternative when, in his play, Mulan Joins the Army for Her Father’, he gives her the surname Hua. Others using The Ballad of Mulan as their guide have attributed her surname to be Mu.

Her name has long been synonymous with the word “heroine”, yet opinions differ as to whether this is her real name. According to Annals of the Ming, her surname is Zhu, while the Annals of the Qing say it is Wei. Xu Wei offers yet another alternative when, in his play, Mulan Joins the Army for Her Father’, he gives her the surname Hua. Others using The Ballad of Mulan as their guide have attributed her surname to be Mu.

There is also some confusion concerning her place of origin and the era in which she lived. She is said by some to have come from the Wan County in Hebei, others believed she came from the Shangqiu province in Henan and a third opinion is that she was a native of the Liang prefecture in Gansu. One thing seems certain though. Hua Mulan w as from the region known as the Central Plains.

Cheng Dachang of the Song Dynasty recorded that Hua Mulan lived during the Sui and the Tang Dynasties. Song Xiangfeng of the Qing Dynasty asserted that she was of Sui origins (AD 581-618) while Yao Ying, also of the Qing Dynasty, believed she was from the time of the Six Dynasties. No record of her achievements appears in official his tory books prior to the Song times. Stories circulated in China’s Central Plains indicate that she must have lived before the Tang Dynasty.

Both history books and legends do at least agree on one thing – her accomplishments. It is said that Hua Mulan’s father received an order to serve in the army. He had fought before but, by this time, was old and infirm. Hua Mulan knew it was out of the question for her father to go and her only brother was much too young. She decided to disguise herself as a man and take her father’s place.

The troops fought in many bloody campaigns for several years before they obtained permission to return home. Hua Mulan was summoned to the court by the emperor, who wished to appoint her to high office as a reward for her outstanding service. Hua Mulan declined his offer and accepted a fine horse instead.

Only later, when her former comrades in arms went to visit her, did they learn that she was a woman.

The story of Hua Mulan is well known and has provided much inspiration for poetry, essays, operas and paintings, as well as the Disney movie.

Wu Zetian: the First Empress in China

Wu Zetian was born in 624. Her parents were rich and of noble families. As a child she was taught to write, read the Chinese classics and to play music.

a child she was taught to write, read the Chinese classics and to play music.

At the age of fourteen, this accomplished child became a concubine to Emperor Taizong. She was given the title Cairen (a fifth grade concubine of the Tang Dynasty). Her perspicacity set her apart from others in the palace and her knowledge of literature and history and talent quickly found favor with the emperor. He bestowed Wu Zetian the title Meiniang which means “charming lady” and she was assigned to work in the imperial study. Here she was introduced to official documents and quickly became acquainted with affairs of state.

In 649, when she was twenty-six years old, the emperor died. He was succeeded by his son Gaozong and following the established court procedures, the old emperor’s concubines were sent to a nunnery to live out their days. Emperor Gaozong was fascinated by Wu’s talent and beauty and frequently visited her in the nunnery. After a period of some two to three years, she was summonsed to the palace and given the title Zhaoyi, the second grade concubine of the new emperor.

Wu gradually earned Gaozong’s trust and favor. After giving birth to two sons, she began to compete with Empress Wang and the senior concubine Xiaoshu for the favor of the emperor. To achieve her goals, Wu Zetian horrifically killed off other favorite concubines of the emperor, and to get rid of the empress, she murdered her own infant daughter and blamed it on Empress Wang. Of all of these crimes, the emperor knew nothing off.

In 655, Gaozong promoted Wu to the position of Empress in place of the now disgraced Wang. Before long both the former empress and the concubine, Xiaoshu, were put to death due to Wu Zetian’s scheme and Wu’s position was finally secured. Then Wu Zetian began her political career in earnest for her goal was to become the first female-emperor of China.

Folk Arts and Festivities-Chinese New Year

Chinese New Year, also known as the Spring Festival, is the biggest holiday in China. Recorded in Li Ji – Yue Ling, Chinese New Year is the time when “air pressure of the sky comes down and air pressure of earth goes up. When heaven and earth connects, all things geminate.” This summarizes the main features of folk art works on Chinese New year, which are heaven and earth, yin and yang, propagation and harvest.

Chinese New Year window decoration usually bears the same implication as for wedding ceremonies. The best I have seen is the paper-cut on the cave windows on the loess plateau. On New Year’s Eve, people put on brand new white window liner. Above the crossbar of the cave window is considered the sky. On the center of the crossbar is a large ball flower of “Baby with coiled hair holding a pair of fish,” a “Revolving flower ” indicating that life revolves around the sky. Below the crossbar is the 36 window lattice. A totem animal (a tiger or a deer) takes the middle four lattice, and other window decorations fill the rest to form a diamond square design with end flowers on four corners. It is similar to the “Thirty-six window lattice of clouds” on wedding occasions, or the “Eight diagram window.” Themes of those paper-cuts include “Two dragons playing with a ball,” “Two phoenixes playing around a peony;” “A golden clock over a frog;” “A deer and a crane;” “A snake twining round a rabbit;” “A vulture catching a rabbit;” “A dragon, a tiger and a vulture;” “Lion playing with a silk ball;” “A rooster holding a fish in the mouth;” “A rat bit open the sky;” “A bowl of Pomegranate;” “Buckled bowl in the shape of two frogs;” or of two fish, two tigers or two rats, “Fairy fish vase;” “Paired tiger vase;” “The Eight diagram fish;” “Deer head” etc. There are also a variety of paper-cuts with the theme of life and propagation: “A snake twining round nine eggs;” “treasure toad;” “A pair of toad;” “frog carrying a rock.” It is a colorful picture of a legendary animal kingdom with birds flying, fish jumping, people laughing and horse soaring. Inside the cave, the kang is decorated with “Border flowers,” across the dish rack is a row of “Dish rack clouds,” and in the center of the ceiling is a large ball flower of “Phoenix playing around peony,” and on the lintel is “Baby holding hands” or “Baby of sun flower seed.”

In Shandong, the lower stream of the Yellow River, it is a whole different taste. The main subject of Chinese New Year paper-cut is the flower of life which grows high from a water pot or a fish bowl. Paper-cuts of the flower of life in a water vase, or the tree of life in a water pot, are pasted across the lintel. Similar paper-cut is also popular in northern Suzhou, south of the Yellow River, all the way to the Yangtze River valley.

In Shandong, the lower stream of the Yellow River, it is a whole different taste. The main subject of Chinese New Year paper-cut is the flower of life which grows high from a water pot or a fish bowl. Paper-cuts of the flower of life in a water vase, or the tree of life in a water pot, are pasted across the lintel. Similar paper-cut is also popular in northern Suzhou, south of the Yellow River, all the way to the Yangtze River valley.

Nowadays urban residents like to paste Chinese New Year paper-cut letter “Fu” (good fortune) upside, as “fu dao” (good fortune arrives). Actually, the diamond square of upside down letter “Fu” was meant to be a rotating symbol for perpetual life.

In Inner-Mongolia, Chinese New Year door-god paper-cut is a pair of deer or a pair of roosters. In central Shaanxi, it is two tigers, and in Henan two monkeys, or cows, or two babies with coiled hair riding a golden cow. These paper-cuts are made with yellow glossy paper, a common way to pray for patronage from the totem or legendary animals for family safety and keeping away evil spirits and disasters.

Chinese New Year is the “beginning of a year, everything starts fresh and gay.”Every household changes a new woodcut of New Year picture. Polytheism that has been widely accepted by Chinese folks believes that every living creature has a power of its own. Such belief can be seen in some of the art works too. New Year picture featuring all types of gods are put out at Chinese New Year time for safeguard. On the 23rd of the twelfth lunar month is to worship the cooking stove, replacing a year old woodcut of “stove god” with a new one for the New Year. Pasted on the two door leaves are two famous warriors from the Tang dynasty, door god “Shentu” and “Yulei,” carrying reed ropes ready to kill any approaching demons. On the shrine by the door steps is god of land; in the yard are gods from ten directions; above the stove is god of wealth; and by the well is god of the well. In Yunnan, Yi and Bai ethnic groups culture has over 100 different images of gods for safeguard, each having a designated function.

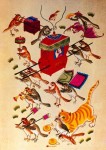

7th of the first Lunar month is the “Human Day,” the day the rat, god of propagation, marring off a daughter. Women would hide their basket of needlework to avoid being bitten by the rat. Big paper-cut “Rat marrying off a daughter” can be seen on the wall in every household on the Human Day. Other areas where birds are worshipped, like Sichuan, it is the “Sparrow marring off a daughter.” The 15th of the first lunar month is the Lantern Festival. Every household folds paper lanterns in a square or a diagram shape, fully decorated with colorful paper-cuts. Types of the lanterns vary from geographically related legendary animals to geometry symbols of life and propagation, such as “The moon lantern;” “Baby with coiled hair lantern;” “The eight diagram lantern,” to name a few.

In the south of Yangtze River valley, between 1st-15th of the first lunar month, people have large gatherings to invite, dance for, and send off exorcists. It starts with going to an exorcist temple to request the mask of exorcist for a baptismal ritual. In Miao ethnic group area, it is the Chinese New Year outdoor gathering in the countryside, when young men and women in festival customs bearing embroidery totem animals and life symbols, playing music instrument (a toad shaped wind instrument), singing and dancing. Such festivity is actually a cultural extension from the ancient custom of worshipping heaven and earth at the suburb of the capital.

Four Roles of Peking Opera:Sheng, Dan,Jing and Chou

subdivision.

subdivision.

Sheng is a grown-up male. It can be further divided into four types. First, lao sheng playing middle-aged or old men with beard. A lao sheng can be of a type specializing in singing, or a type specializing in martial arts. Lao sheng is the most common male character in Peking Opera. Cheng Changgeng and Tan Xinpei, regarded as founders of Peking Opera, were both lao sheng players. Second, wu sheng, or man with martial skills. A wu sheng can specialize in long weapons or short weapons. The long-weapon wu sheng wears armor, looks dignified and has a moderate skill of singing and recitation, whereas the short-weapon wu sheng wears short clothes and is swift of action. Third, xiao sheng playing young handsome men, most of whom are scholars. This character is frequently portrayed in love stories. Xiao sheng can be further divided into gauze-hat sheng (a court official), fan xiao sheng (scholar using a fan), pheasant-feather fan sheng (a handsome young man), and a poor sheng (a scholar failing to become an official). And fourth, hong sheng playing characters with a red face such as Guan Yu and Zhao Kuangyin.

Owing to the uniqueness of Peking Opera, the role of xiao sheng had long been relatively unimportant. While many plays give prominence to lao sheng and dan (female) roles, xiao sheng is relatively obscure. In the history of Peking Opera, well-known actors playing the xiao sheng role were few in number. Earlier acclaimed xiao sheng players were Cheng Jixian (1874-1944), Jiang Miaoxiang (1890-1972) and Jin Zhongren (1886-1950). Later renowned players were Yu Zhenfei (1902-1993) and Ye Shenglan (1914- 1978). Among xiao sheng impersonators, the only one able to play in shows xiao sheng is the hero was Ye Shenglan.

This is quite different from Western operas where the young hero is very important and is played by highly acclaimed actors. In performance, xiao sheng’s most striking feature is singing and recitation with a combination of real and false voices. His falsetto is relatively high-pitched and fine, making the role distinctively different from lao sheng. On the other hand, xiao sheng’s falsetto is different from that of the dan (female) role. It should be strong but not rough. And it should not be as soft and gentle as a woman’s voice. Fine-tuning nuances in a xiao sheng’s singing is difficult. This is why not many actors have excelled in playing this role like Ye Shenglan.

Dan is a general term for female characters. The gentle and quiet is called qing yi and usually represents orthodox yong women. The vivacious is called hua dan and represents girls of ordinary households or extroversive disposition. There are also lao dan (old female), wu dan (female with martial skills) and cai dan which used to be played by male actors. Only “painted face,” or jing, usually has facial makeup. They are all male with a rough, bold and uninhibited character. They speak loudly, shout at the slightest provocation and, if irritated, may use force. The jing roles are divided, too, into the “Singing-oriented” type, or wen jing, and the “martial” type, or wu jing. Actors impersonating jing commonly paint their faces in various styles that range from a single color to be wildering combinations and patterns.

Read the rest of this entry »