The Stage and Props of Peking Opera

In an early period, Peking Opera was staged on an interesting stage. The front of the stage extends forward, with three sides facing the audience. The other side is the backstage. An embroidered curtain hangs across the backstage, and on each side of the curtain is a curtained door for performers to enter or exit the stage. Coming onto the stage from the entrance door, an actor with full makeup and costume begins to play his role; at the conclusion of his performance, he goes off the stage through the exit door. This means the end of a show or transition into another part of a play. After 1908, which saw the appearance of modern theaters and the use of setting in Shanghai, people called the old-style stage curtain shoujiu.

of the stage extends forward, with three sides facing the audience. The other side is the backstage. An embroidered curtain hangs across the backstage, and on each side of the curtain is a curtained door for performers to enter or exit the stage. Coming onto the stage from the entrance door, an actor with full makeup and costume begins to play his role; at the conclusion of his performance, he goes off the stage through the exit door. This means the end of a show or transition into another part of a play. After 1908, which saw the appearance of modern theaters and the use of setting in Shanghai, people called the old-style stage curtain shoujiu.

Shoujiu was made of cloth or satin and embroidered with exquisite patterns. It served as setting but was not limited by operas being performed. It was more like a leading actor’s signboard. Every famous actor had his representative shoujiu. Mei Lanfang (1894-1961), for example, used a curtain embroidered with plum blossoms, peonies and peacocks; and Ma Lianliang (1901-1966), a well-known actor who usually played old people, had a stage curtain embroidered with a set of Han Dynasty horsedrawn chariots.

Shoujiu was made of cloth or satin and embroidered with exquisite patterns. It served as setting but was not limited by operas being performed. It was more like a leading actor’s signboard. Every famous actor had his representative shoujiu. Mei Lanfang (1894-1961), for example, used a curtain embroidered with plum blossoms, peonies and peacocks; and Ma Lianliang (1901-1966), a well-known actor who usually played old people, had a stage curtain embroidered with a set of Han Dynasty horsedrawn chariots.

On the stage are placed props of a decorative nature, usually a table and two chairs. An imaginary room comes with the presence of a table and two chairs. In the mind of the audience, the space around the table and chair may be a palace, a study, a court where suspects are tried, or a military commander’s tent. Or it can be a boisterous restaurant. The difference lies in details in the decoration of the table and chairs. If it is a palace, the table curtain will have dragon patterns; if it is a study, the table curtain will be of a light blue or light green color and embroidered with several orchids.

A lot of learning goes into how to place the table and chair. If the chair is placed behind the table, it shows a solemn occasion: an emperor holds court, an official officiates, or a general handles military affairs. If the chair is placed in front of the table, it shows an ordinary household’s daily life.

There is another interesting point. Chairs on the stage all have cushions, which are of different thickness. Why? In Peking Opera, different characters wear shoes with soles of different thickness. A sheng or jing character wears thick-soled shoes (as thick as 20cm), whereas dan and chou characters wear thin-soled ones (1-2 cm). And different characters are required to have different sitting postures. A dan character should really sit on the cushion; whereas a sheng character should sit on the edge of the chair; and a chou (clown) character may move about or even squat on the cushion. The table can serve as a bed, a support for observing a distant object from a great height, a bridge, a gate tower, a mountain, or even a cloud. The chair can serve as a weapon for characters. In Peking Opera, such a simple method is used to portray a rich plot. When enjoying Peking Opera, it is not necessary to seek realness. Audiences are given great room for imagination. “A table and two chairs” has become a symbolic mark of Peking Opera’s “less is more” way of portrayal.

Characters in Peking Opera often ride horses. Audiences will not see a real horse on the stage. Instead, a character holds a riding whip with tassels to show he is on a horse. This is another example of the extensive use of symbols in Peking Opera. There is not a real horse on the stage, but the actor has to portray his riding posture in a distinctive and graceful way. A riding whip gives an actor the greatest freedom for acting. With different pantomimic gestures with the whip, he can show a galloping horse, a horse with a drooping head, a horse that remains at the same place after running for half a day, or a horse that has traveled thousands of miles in a twinkle.

A riding whip is a tangible stage prop. In Peking Opera there are also props of a virtual type. In Picking up a Jade Bracelet (shi yu zhuo), for example, a girl stitches a cloth shoe sole. While the sole is real and tangible, the needle is imaginary. In the hand of the actress, the absence of a needle is better than an actual needle. Another example is a dinner party. A host orders “setting the table.” Waiters immediately carry a wine pot and glasses onto the stage. The host and guests begin drinking glass after glass. But audiences do not see real wine, rice and dishes. The actors on the stage do not really drink and eat. But soon they all are “full”. In Peking Opera, kitchen utensils are not usually carried onto the stage.

Stage props, big and small, as well as simple setting in Peking Opera, including candlesticks, lanterns, oars, letters, paper, ink, writing brushes, ink slabs and pavilions, are not made of genuine materials — they play a symbolic role only. A great variety of weapons as well as flags carried by guards of honor are not real, either, though they bear a similarity to real things. A Peking Opera is usually divided into several acts. Traditionally, when there is a change of acts, a group of men called stage checkers would change the setting. Wearing long gowns but no facial expression whatsoever, they would come onto the stage after an act is over, reshuffle the table and chairs, indicating a change of place and time, and leave the stage in silence. Sometimes, they would produce some stage effect. In Inter-linked Military Tents (lian ying zai), for example, to show Liu Bei making his escape in a conflagration, a stage checker standing on the side of the stage would light pieces of paper and throw the burning paper onto the actors, who thereupon do escaping or extinguishing acts — feats worthy of acrobats.

Traditional stage setting is part of Peking Opera’s conventions. Many foreign audiences are very curious about Peking Opera’s highly stylized performances. In Peking Opera, two pieces of cloth represent a sedan chair; a push and a pull by an actor means opening and closing a window. People watching Peking Opera for the first time may find it difficult to understand. Also, Peking operas are closely connected with the history, customs, culture and social conditions of China. To enjoy Peking Opera, audiences need to understand China, its his tory and culture.

Today, a big silk curtain hangs before a Peking Opera stage. A show begins when the curtain rises. This curtain does not come down until the whole show comes to an end. Between acts, a second curtain made of satin rises and closes. This “double curtain” practice is the result of a reform in the 1950s when the reshuffle of table and chairs on the stage between acts by a group of checkers in full view of the audience was abolished.

Liaoning Provincial Museum

Address: Liaoning Province, Shenyang City, Heping District, Shiwei Road, #26

#26

The Liaoning Provincial Museum is located in Heping District of Shenyang City, Liaoning Province. The area of the Museum grounds and buildings totals 110,000 square meters. The heart of the Museum is a three-story exhibition hall that was designed by a German architect. In 1988, a new three-story white building was built inside the grounds that include a large hall and a surrounding corridor. Historical artifacts and ancient arts are the main focus of the Museum’s collections. These include some eighteen categories of objects: paintings and calligraphy, embroideries, woodblock prints, bronzes, ceramics, lacquerware, carvings, oracle bones, celadons, costumes, archaeological material, coins and currency, stelaes, old maps, ethnic minority artifacts, revolutionary artifacts, furniture, and assorted other items. Among these some were excavated and others were passed down through the ages that are inherited, not recovered from the earth. The collections occupy an important position among museums’ collections in China.

Painting and calligraphy collections include paintings by famous Tang-dynasty and Northern Song artists, and woodblock-print editions include the Ming-dynasty Album of the Ten-bamboo Studio, the first colored woodblock print in Chinese woodblock-print history. The ceramics collections in the museum are also quite famous and valuable. Liao porcelain is unique in the art form for its treatment of colored glazes, but the collection also includes Liao monochromes such as the lovely Liao white porcelain. Many of the ceramic forms embody nomadic characteristics, and the glazes and colors are imbued with local character. Production methods continue the traditions of the Tang and Five dynasties kilns. Two permanent collections are on display in the museum. One is an exhibit on Chinese history, and the other is a display of stone inscriptions. The former deals with overall Chinese history in general but also takes local Liao history into special consideration. Contents include:

Room 1: The main archaeological findings from Paleolithic and Neolithic times in the Liaoning region. Key emphases are on the sites from early Paleolithic times at Yingkou Jinniu Shan, the Paleolithic cave site at Hezi Cave, the Hongshan Culture site, the Shenyang Xinle early Neolithic site, the Lushun Guojia Cun site, and so on.

Room 2: Key exhibits include a Xiajiadian Lower-level-culture site that corresponds to Xia and Shang periods that was discovered in Liaoning, several sites that have produced Shang and Zhou bronzes, and bronze daggers and swords that accom-panied burials, etc.

Rooms 3 and 4: Show items from the period of Warring States, Qin, and Han.

Rooms 3 and 4: Show items from the period of Warring States, Qin, and Han.

Rooms 5, 6, and 7: Show items from the Three Kingdoms, the East and West Jin, the North and South dynasties. Most importantly, on exhibit here are the tomb wall paintings of Liaoyang.

Room 8: Is the exhibition hall for Sui, Tang, and the Five dynasties. The main objects on display were excavated from a Tang-dynasty grave discovered in Chaoyang, also a group of artifacts from the Bohai Kingdom, which include a group of rarely seen earthen statues.

Rooms 9 to 12: Are exhibitions for Liao, Song, Jin, and Western Xia. A key emphasis is the exhibition of items from some extraordinary Liao tombs. Also on display is a farmer ’s house site from the Jin dynasty, as well as Liao, Song, and Jin ceramics.

Rooms 13 to 18: Exhibit Yuan, Ming and Qing objects. These include Ming-dynasty maps, an inscription from a military commander of the Ming, from eastern Liaoning, also Ming-and-Qing-dynasty ceramics and paintings.

In addition to the above exhibitions, a corridor of stelaes has been set up on the east side of the exhibition hall. This preserves a collection of tomb stones set up from the Han to the Ming dynasties, as well as inscription-stelaes, stone portraits, stone coffins and so on, altogether some one hundred stone objects. One of the important pieces is a Northern-Wei inscription by a famous calligrapher of the time who lived from 386-534 AD.

the east side of the exhibition hall. This preserves a collection of tomb stones set up from the Han to the Ming dynasties, as well as inscription-stelaes, stone portraits, stone coffins and so on, altogether some one hundred stone objects. One of the important pieces is a Northern-Wei inscription by a famous calligrapher of the time who lived from 386-534 AD.

Nanjing Museum

Address: Jiangsu Province, Nanjing City, Zhongshan East Road, #321

The Nanjing Museum is located inside the Zhongshan Gate of Nanjing City. Its predecessor was known as the Central Museum Preparatory Location. The complex of buildings represents an amalgamation of east and west, with the great hall copying the style of a Liao-dynasty palace. The Museum currently holds some 400,000 objects in its collections, among which are some of the most famous objects in China. These include the only complete set of ‘jade suits sewed with silver thread’ in China, which are world renowned. In 1982, a Warring States period Chu State tomb was excavated from which stellar  pieces were retrieved that also form some of the extraordinary treasures in this museum.

pieces were retrieved that also form some of the extraordinary treasures in this museum.

The calligraphy and paintings collections are also very special. Among the 100,000 objects that have officially entered the collections, most are Ming- and Qing-dynasty works of artists who lived in the Jiangsu area. Among these, the most special are the ‘Wu Men painting school,’‘Yangzhou painting school,’ Jinling painting school,’as well as a small number of Song and Yuan-dynasty works. Most of the representative works of the modern Chinese painter Fu Baoshi (1904-1965, painter, art historian), and Chen Zhifo (1896-1962, modern arts educator) are stored here. The Nanjing Museum holds the objects excavated by archaeologists in the early part of the twentieth century that were moved to Nanjing when the Palace Museum moved southward. These include excavations in Heilongjiang, Xinjiang, Yunnan, Sichuan, Gansu and other the Nanjing Museum. A south-of-Yangtze family’s living room displayed in the Nanjing Museum places. Collections also include artifacts from the southwest parts of China of the Naxi tribe, the Yi tribe, the Miao tribe, and other national minorities. The Museum applies modern scientific methods of conservation, and is active in displaying its holdings, having mounted some 236 exhibitions.

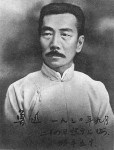

Lu Xun (Zhou Shuren)

“For all of ignorant people of a nation, even if their body is somehow strong, somehow grand, even then they can only make meaningless displays [of this “strength”]. [As for] the multitude of constituents and observers, however many may die from [this] sickness, this is [still] not to be considered as unfortunate.”

From the preface of Lu Xun’s work Na Han (Call to Arms)

Note: Lu Xun was a doctor before he became a writer. Once he saw on a film a Chinese being executed by Japanese while many other Chinese were watching this “spectacular event”. This made him felt that saving the “souls” of people is more important than saving their bodies.

Lu Xun, was the pen name of Zhou Shuren (September 25, 1881 – October 19, 1936) is one of the major Chinese writers of the 20th century. Considered by many to be the founder of modern Chinese literature, he wrote in baihua (the vernacular) as well as classical Chinese. Lu Xun was a short story writer, editor, translator, critic, essayist and poet. In the 1930s he became the titular head of the Chinese League of Left-Wing Writers in Shanghai.

19, 1936) is one of the major Chinese writers of the 20th century. Considered by many to be the founder of modern Chinese literature, he wrote in baihua (the vernacular) as well as classical Chinese. Lu Xun was a short story writer, editor, translator, critic, essayist and poet. In the 1930s he became the titular head of the Chinese League of Left-Wing Writers in Shanghai.

Lu Xun’s works exerted a very substantial influence after the May Fourth Movement to such a point that he was lionized by the Communist regime after 1949. Mao Zedong himself was a lifelong admirer of Lu Xun’s works. Though sympathetic to the ideals of the Left, Lu Xun never actually joined the Chinese Communist Party. Lu Xun’s works are known to English readers through numerous translations, especially Selected Stories of Lu Hsun translated by Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang.

Early life

Born in Shaoxing, Zhejiang province, Lu Xun was first named Zhou Zhangshou, then Zhou Yucai, and finally himself took the name of Shùrén, figuratively, “to be an educated man”.

The Shaoxing Zhou family was very well-educated, and his paternal grandfather Zhou Fuqing held posts in the Hanlin Academy; Zhou’s mother, née Lu, taught herself to read. However, after a case of bribery was exposed – in which Zhou Fuqing tried to procure an office for his son, Lu Xun’s father, Zhou Boyi – the family fortunes declined. Zhou Fuqing was arrested and almost beheaded. Meanwhile, a young Zhou Shuren was brought up by an elderly servant Ah Chang, whom he called Chang Ma; one of Lu Xun’s favorite childhood books was the Classic of mountains and seas.

His father’s chronic illness and eventual death during Lu Xun’s adolescence, apparently from tuberculosis, persuaded Zhou to study medicine. Distrusting traditional Chinese medicine (which in his time was often practised by charlatans, and which failed to cure his father), he went abroad to pursue a Western medical degree at Sendai Medical Academy (now medical school of Tohoku University) in Sendai, Japan, in 1904.

Education

Lu Xun was educated at Jiangnan Naval Academy (1898-99), and later transferred to the School of Mines and Railways at Jiangnan Military Academy. It was there Lu Xun had his first contacts with Western learning, especially the sciences; he studied some German and English, reading, amongst some translated books, Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics, J. S. Mill’s On Liberty, as well as novels like Ivanhoe and Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

On a Qing government scholarship, Lu Xun left for Japan in 1902. He first attended the Kobun Gakuin (Kobun Institute) (Hongwen xueyuan), a preparatory language school for Chinese students attending Japanese universities. His earliest essays, written in Classical Chinese, date from here. Lu also practised some jujutsu.

Lu Xun returned home briefly in 1903. Aged 22, he complied to an arranged marriage with a local gentry girl, Zhu An. Zhu, illiterate and with bound feet, was handpicked by her mother. Lu Xun possibly never consummated this marriage, although he took care of her material needs all his life.

Read the rest of this entry »