The Book of Poetry

The Book ot Poetry is the first anthology of Chinese poems. It compiled 305

The-Book-of-Poetry poems written over a period of 500 years spanning from the beginning of Western Zhou Dynasty to the mid-Spring and Autumn Period. The Book of Poctly has three parts: Feng (Songs), Ya (Odes and Epics) and Song (Hymns). Feng includes 160 songs sung by people in 15 city states. Ya includes 105 poems in two parts: “The Book of Odes” and “The Book of Epics.” Song includes 4o poems in three parts: “The Hymns of Zhou,” “The Hymns of Lu,” and “The Hymns of Shang.”

“The Book of Songs” (Feng) is the most significant segment of The Book of Poetry The folksongs of the Zhou Dynasty collected into “The Book of Songs” recount the real life of common people, and express people’s indignation about oppression and their yearning for a happy life. “The Book of Songs” is the wellspring of Chinese realist poetry.

“The Life of Peasants” faithfully captures the wretched lives led by enslaved people. The “Woodcutter’s Song” rouses the slave class to awareness. The angry slaves call the slave owners to account: “How can those who neither reap nor sow have three millions sheaves on their plate? How can those who neither hunt nor chase have in their courtyard the game of each race?” Some poems even describe the direct resistance of slaves to the ruling class, Such as “The Large Rat”. Some poems in “The Book of Songs” capture the trauma caused by forced military service and conscripted labor, for example, “My Lord, My Man is Away, ” and “Returned.” Some love poems in “The Book of Songs” reflect women’s anguish at being forced into marriage and recall young people’s longing and search for happy marriage, as in “A Faithless Man” and “A Rejected Wife.” “Depression,” another love poem, even discloses a deep awareness of resistance. “A Shepherdess” and “Gifts” wish good cheer and call for optimism. All of the poems in “The Book of Songs” are honest expressions of laboring people’s thoughts and feelings.

Many folksongs in “The Book of Songs” criticize and satirize the ruling class’s decadent and promiscuous lifestyles, for example, “Incest”, “The Duke’s Mistress” and “Complaint of a Duchess.”

The most distinctive artistry in “The Book of Songs” lies in its realistic depiction of objects in simple language, mirroring social reality with glimpses of ordinary life. Characterization in “The Book of Songs” is also realistic: authors voice character’s joys and sorrows through the direct expression of their inner feelings. Most poems in “The Book of Songs” were written in three-character lines, rhyming every other line, but there were also five- and seven-character lines as well as lines of irregular length. For example, “The Woodcutter’s Song” was written in the form of irregular lines, that change along with the rising emotions and have distinct rhymes and musical quality. The language used in “The Book of Songs” is focused, elegant and lively. The skilled application of double-adjectives, rhyming words and alliterations enhance the songs’ artistic appeal. The adoption of the expressive techniques of fu (descriptive prose interspersed with verse), bi (metaphor) and Xing (evocation) greatly reinforce its illustrative power.

Poems in Ya (ode and epics) and Song (hymns) were used by the ruling class for specific occasions. Although they could not match the poems in “The Book of Songs” in their ideological content, they reflected some aspects of social life and therefore also had certain social meaning.

The Book of Poetry splendidly signals the onset of Chinese literature. Its spirit of realism has exerted great influence on the literature of later times. The Book of Poetry enjoys a high reputation in both China’s and the world’s cultural history.

Thangka of the Tibetans, an Integration of Religion and Art

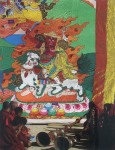

Everywhere in the vast regions inhabited by the Tibetan ethnic group in western China, whether in monasteries, temples or average homes, a painting with bright colors, rich content and noble qualities can be seen. It is similar to the painted scrolls of the Han nationality, which are hung on walls. This fine art is Thangka.

western China, whether in monasteries, temples or average homes, a painting with bright colors, rich content and noble qualities can be seen. It is similar to the painted scrolls of the Han nationality, which are hung on walls. This fine art is Thangka.

The gorgeous Thangka is the gem of the painstaking efforts of Buddhist artists and master painters. It serves as decorations for homes and monasteries, as well as reflecting the pious beliefs of the Tibetan people.

Thangka is a unique form of painting in Tibetan culture. “Thangka” is a transliteration from the Tibetan language, meaning “cloth or silk painting scroll capable of being spread for appreciation.” It originated in the Tobon period (ancient Tibet) around the 7th century. According to legend, the earliest Thangka was a portrait of Goddess Lhamo, which was painted by Songtsan Gambo (c.617-650), king of Tobon. The Bonist culture of Tibet, the inscriptions on precipices and the introduction of Buddhism into Tibet were all factors in expediting the birth and development of Thangka. Boasting distinct national features, strong religious colors and unique artistic style, Thangka has always been regarded by the Tibetans as a treasure.

Thangka has a multitude of qualties, but most Thangka paintings are done on cloth and paper and are called painted Thangka. In addition, there are woven Thangka, which encompass a dozen varieties, including pearl Thangka, color-painted Thangka, embroidered Thangka and brocade Thangka.

Thangka has a multitude of qualties, but most Thangka paintings are done on cloth and paper and are called painted Thangka. In addition, there are woven Thangka, which encompass a dozen varieties, including pearl Thangka, color-painted Thangka, embroidered Thangka and brocade Thangka.

Painting Thangka is a serious matter because it is seen as a practice in adhering to the doctrine of Buddhism. The process of painting is an act of giving to kindness and of practicing virtue and Buddhist doctrine-not the artist’s self-expression of his will. Therefore, the painter must follow a fixed pattern and often has to practice Buddhism for a few days before painting. Some will conduct religious ceremonies and chant Buddhist scripture. Tibetan painters rarely leave their names on the paintings.

It is extremely complicated to paint a Thangka; the act of doing so often lasts several months and even years. It involves many complex procedures, including linearization, colorization, dyeing, contour-sketching with color brushes, tracing designs in gold and inlaying gold.

In painting, the artist uses a fine thread to fasten the cloth onto a wooden frame and applies glue evenly on both sides of the cloth. He coats it with another layer of gypsum powder after it has been air-dried and uses shells and pebbles to polish it until the cloth’s surface is smooth and even, revealing no grains. Then, he uses a carbon stick to sketch the contours of the Buddha and uses a pencil to draw the lines. Pure natural mineral dyestuffs are used, which are bright and durable. It is necessary to use a brush dipped in color to do contour sketching after the application of color and then a gold juice to depict the portrait. Tibetan painters are extremely selective about the quality of the gold powder; it must be pure gold.

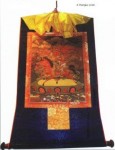

Great attention is also paid to the mounting process once the painting is complete. The four sides of the painting are bordered with multicolored brocade and the top and bottom are fastened with a wooden roller. Many Thangkas have red and yellow borders added and are covered with silk the same size as the painting.

After mounting, Thangkas that incorporate Buddhism are usually sento to a temple or monastery for a consecration ceremony and lamas are invited to chant scriptures and add their fingerprints with gold juice or cinnabar on the back of the painting. This way, a Thangka becomes a holy article.

Aside from religious subject-matter, Thangkas also depict Tibetan medicine, historical events, biographies, customs, legends and fairy tales, involving politics, economy, history, religion, literature, art, and social life. Thus, Thangkas are like an encyclopedia of the Tibetans.

The size of Thangkas varies. The smallest is only the size of a palm, painted on paper, cloth or goat skin; the large ones can be as large as dozens and even hundreds of square meters. When such a huge Thangka is slowly unfolded it can cover a hill slope. A large Thangka titled “A Show of Colored Drawings on Literature and Art of Tibetan Ethnic Group of China” is 618 meters long and took 400 top-level handicraft masters nearly four years to complete.

Developed from the 7th century to the present, Thangka has become a very mature art of painting as well as a religious art. The Buddha and Bodhisattvas painted on Thangkas have replaced sculptures and murals in the monasteries and temples and have become portable idols. As long as the Tibetans who wander in search of water and grass on the vast, desolate plateau roll up a Thangka and hang it in the tent in which they live, they will be able to pray, conduct religious services and receive spiritual sustenance.

Henan Museum

Address: Henan Province, Zhengzhou City, Nongye Road, #8 flowering crabapple style ceramic flower pot unearthed in Yu. A rose-purple Chinese flowering crabapple style ceramic flower pot unearthed in Yu.

The Henan Museum is one of China’s oldest museums. It is a ‘key’ museum, with modern displays and exhibitions, modernized equipment, and a unique architecture. In 1961, along with the move of the provincial capital to Zhengzhou, it moved to its current location. In 1991 that museum was remodeled and in 1999 the official reopening was held, when the name was officially declared the Henan Museum.

The new Henan Museum is set in the central section of Nongye Road in Zhengzhou City, Henan Province. It covers an area of more than 100,000 square meters, with a building area of 78,000 square meters. The exhibition hall space is more than 10.000 square meters. The building uses a combination of both traditional architecture and path breaking new technology.

A Warring States period gold-plating silver belt hook inlaid with jade unearthed in Hui County, Henan Province. Henan is situated in the middle reaches of the Yellow River. Its ancient name is Zhongzhou, or central region. It is one of the important areas for the rise of the Chinese people’s early civilization. Because of this, exhibitions in this museum are mostly related to the ancient history and culture of the Henan region, including objects, historical traces, ancient architecture, archaeological discoveries and arts and crafts.

In the past several decades, the collecting, protection, research, and exhibition of this museum’s artifacts as well as their promotion. Objects from the Museum’s collections have traveled to America, Japan, England, Germany, France, Australia, and Denmark for exhibition and have been widely praised. The Henan Museum applies modern management systems, its security systems of surveillance and alarms are consolidated into a central unit, to ensure the safety of the objects. The automatic management system of the buildings can monitor and adjust all of the surveillance and condition systems of the various buildings. This enables ambient environmental conditions to be monitored and adjusted, to protect the collections and exhibited objects and to control the required levels of temperature and humidity.

Zeng Houyi Bells: Gem of Ancient Chinese Art

The set of bells, set of chimes and other instruments excavated from the tomb of Zeng Houyi, who was a Warring States duke in Suixian County (now Suizhou City in Hubei Province), are the largest-scale ancient percussion instruments found so far. The musical instruments were discovered in the central chamber, which was the biggest, and the second biggest, the eastern chamber.

Among the musical instruments found was a bell used for tuning other instruments, a ten-stringed plucked instrument, five Se (a zither-like instrument) with 25 strings each, two Yu (or Sheng) and one hanging drum. The other instruments found were three Xiao (a reed instrument consisting of a bundle of 13 flutes, each of different thickness), two Chi (a flute with a closed tube, blown transversely, with the air exit on top, and the five finger holes open “forward”– toward the player. The method of playing the Chi, by opening and closing holes, bespeaks a close relationship with the ocarina), seven 35-stringed Se and a small drum. The most distinguished among them were Zeng Houyi bells — the gem of ancient Chinese Art:

The Zeng Houyi Bells (big photo)

The Zeng Houyi bells are a three-tiered set which has 65 refined bronze bells, including a large Jian drum (90cm in diameter, the drum was suspended from a framework in such a way that the drum head faced the striker), one set of bells and one set of chimes. They formed the three sides of a rectangle.

The musical range of the Zeng Houyi bells, which can carry the main melody as well as the harmony, was more than five octaves, and of these three distinct groups have 12 complete notes each.

All the musical instruments excavated from the Zeng Houyi tomb show superb craftsmanship and function surprisingly well. Indeed, some could not be surpassed even today.

Bells Music list:

The Chime of Bells Music: A Chu Air

[audio:A_Chu_Air.mp3]

The Chime of Bells Music: Ode To The Orange

[audio:Ode_to_the_Orange.mp3]

The Chime of Bells Music: Melody of Chu

[audio:Melody_of_Chu.mp3]

The Chime of Bells Music: Clouds

[audio:Clouds.mp3]

The Chime of Bells Music: Mourning For Ying

[audio:Mourning_for_Ying.mp3]

The Chime of Bells Music: Oracle

[audio:Oricle.mp3]

The Chime of Bells Music: Heroic Air of Chu

[audio:Heroic_Air_of_Chu.mp3]

The Chime of Bells Music (Chinese Song): The Osprey

[audio:The_Osprey.mp3]

The Chime of Bells Music (Chinese Song): The Song of The Yue People

[audio:Song_of_the_Yue_People.mp3]

The Chime of Bells Music (Chinese Song): Song to Righteousness

[audio:Song_to_Righteousness.mp3]

The Chime of Bells Music: Schu Palace Banquet Music

[audio:Schu_Palace_Banquet_Music.mp3]