Posts Tagged ‘Su Shi’

Three Masters Focusing on Temperament and Taste

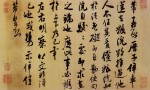

Part of Scroll of a Poem on the Miserable Life in Huangzhou, written in running script by Su Shi. This chapter will introduce three calligraphy masters from the Song Dynasty: Su Shi, Huang Tingjian and Mi Fu, not because they were active in the latter half of the 11th century, and not because they were friends, but because they developed spontaneously a style focusing on the expression of emotion and feelings. Now we introduce them in the order of their ages. Su Shi had extra talents and knowledge and was an outstanding man of letters, painter and calligrapher. His bold poems constitute his own unique school and were praised highly by the people of his age and the people of later generations. He had a good command of the running and regular scripts. But his political life was turbulent, and he was exiled from the capital several times. Once he was slandered and thrown in prison for 130 days. Saved by the empress dowager and key ministers, he survived but was exiled to Huangzhou in south China. One spring day in the third year of his life in Huangzhou, he wrote a poem to describe his misery. Then he turned the poem into the famous Scroll of a Poem on the Miserable Life in Huangzhou. This poem contains 120 characters in 24 sentences. Many changes in the strokes express a profound artistic conception which matches the depression expressed by the poetic lines.

At the beginning, the characters progress slowly, and show even spaces between them. He uses bent strokes, and oblique parts and lines to express his unquiet heart. In the second character on the second line the last vertical stroke is written like a sharp sword, occupying a large space, which exudes boundless feelings. What we see here is part of the work. The last sentence means that he wants to go back to the capital city, but there are nine gates to pass through, and he wants to go back to his hometown, but the tombs of his relatives are far away. With different sizes, these characters show strong contrasts, and demonstrate his unstable mind and resentment, and also his perplexity and pessimism. The shapes of the dots and strokes, their strength, speed, falsity and reality, density and looseness, and the ups and downs of their rhythm and changes show the natural harmony of the whole work.

Su Shi left behind him many poems and brief comments on calligraphy.  “Innocence and romanticism are my teachers, with imagination and creation, I finish my calligraphic works, free from traditional rules. I write dots and strokes freely, without any restrictions.” He once said that he enjoyed handwriting. It was better for old people to write than to play chess, he said. In the postscript written on a calligraphic work by a friend, he said that calligraphy was a game played with strokes. Su Shi loved painting too. The themes of his paintings are not concrete things, but the water, rocks and hills in his mind or the resentment in his heart. Huang Tingjian was a master of poetry and calligraphy. When he was an official he always had trouble, and was exiled from the capital several times. His calligraphic works are powerful and changeable. The characters in his regular and running scripts extend outward. His handwriting in the wild cursive script is better than that of his teachers. Scroll to Eminent Monks (see next page) expresses his unconstrained, straightforward and loquacious nature. Huang Tingjian emphasized gracefulness in his calligraphy. Like Su Shi, he took calligraphy as a game. Mi Fu was also good at poetry and calligraphy. He was brave and unyielding. His personality shows in his unrestrained, light and natural running and cursive script handwriting. His Collection of Tiaoxi Brook Poems in the running script is a good example of this.

“Innocence and romanticism are my teachers, with imagination and creation, I finish my calligraphic works, free from traditional rules. I write dots and strokes freely, without any restrictions.” He once said that he enjoyed handwriting. It was better for old people to write than to play chess, he said. In the postscript written on a calligraphic work by a friend, he said that calligraphy was a game played with strokes. Su Shi loved painting too. The themes of his paintings are not concrete things, but the water, rocks and hills in his mind or the resentment in his heart. Huang Tingjian was a master of poetry and calligraphy. When he was an official he always had trouble, and was exiled from the capital several times. His calligraphic works are powerful and changeable. The characters in his regular and running scripts extend outward. His handwriting in the wild cursive script is better than that of his teachers. Scroll to Eminent Monks (see next page) expresses his unconstrained, straightforward and loquacious nature. Huang Tingjian emphasized gracefulness in his calligraphy. Like Su Shi, he took calligraphy as a game. Mi Fu was also good at poetry and calligraphy. He was brave and unyielding. His personality shows in his unrestrained, light and natural running and cursive script handwriting. His Collection of Tiaoxi Brook Poems in the running script is a good example of this.

Mi Fu’s articles on calligraphy, like his calligraphic works, focus on graceful and romantic touches. By these standards, he assessed the calligraphic works of his predecessors. He even criticized Yan Zhenqing, a calligrapher of the mid-Tang Dynasty, who opened a new chapter for the development of calligraphy, saying that Yan’s regular script handwriting was too plain. Like Su Shi and Huang Tingjian, he believed that calligraphy was a game, saying, “Calligraphy is a game, so it is unnecessary to consider the characters as beautiful or ugly. It is enough if you are satisfied with your work. After you put down the brush, the game is over.”

These three calligraphy masters from the Song Dynasty were influenced by the prevailing cultural trends and aesthetic viewpoints. The Song Dynasty was influenced by the developed culture of the Tang Dynasty, but it met internal and external unrest. The men of letters had less aspirations and progressive enthusiasm than those of the Tang Dynasty. When they found it difficult to realize their high ambitions, they devoted themselves to poetry, calligraphy and other artistic activities exclusively. Opposite to the vigorous and forceful style of the Tang Dynasty, the poetry of the Song Dynasty sought a deep and cold resonance. Tang paintings have landscape, flowers, birds and natural scenes as the background, and beautiful women, cows and horses playing the main roles. But the landscape paintings of the Song Dynasty have natural scenes as the main objects.

Therefore, the people of the Song Dynasty liked the running-script calligraphy, a script between the regular and the cursive scripts – not rigorous like the regular script, and easier to learn and recognize than the cursive script. The running script is convenient for the calligrapher to use his brush, and makes it easy for him to express his peaceful, simple and leisurely mind, and to realize his aspiration to be happy through calligraphy.

The sentiments and interests the Song calligraphers sought are similar to but different from the gracefulness cherished by the Jin calligraphers. Both emphasized the beauty of the image of the objects and the beauty of the interest and charm of calligraphy. But the gracefulness cherished by the Jin masters has a narrow connotation, merely having a peaceful, plain and quiet tone. While playing such an artistic game, the Song calligraphers got rid of all  kinds of shackles and pressures, and created works in a powerful and unconstrained style. They reached the best understanding of the poetry and handwriting, and expressed them in the best way. So the calligraphers took their counterparts from the Jin Dynasty as their teachers but they outstripped their counterparts in purport and techniques. This is obvious from a comparison of the handwriting in the running and cursive scripts by the Song calligraphers with those of the Jin calligraphers.

kinds of shackles and pressures, and created works in a powerful and unconstrained style. They reached the best understanding of the poetry and handwriting, and expressed them in the best way. So the calligraphers took their counterparts from the Jin Dynasty as their teachers but they outstripped their counterparts in purport and techniques. This is obvious from a comparison of the handwriting in the running and cursive scripts by the Song calligraphers with those of the Jin calligraphers.