Thangka of the Tibetans, an Integration of Religion and Art

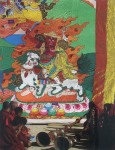

Everywhere in the vast regions inhabited by the Tibetan ethnic group in western China, whether in monasteries, temples or average homes, a painting with bright colors, rich content and noble qualities can be seen. It is similar to the painted scrolls of the Han nationality, which are hung on walls. This fine art is Thangka.

western China, whether in monasteries, temples or average homes, a painting with bright colors, rich content and noble qualities can be seen. It is similar to the painted scrolls of the Han nationality, which are hung on walls. This fine art is Thangka.

The gorgeous Thangka is the gem of the painstaking efforts of Buddhist artists and master painters. It serves as decorations for homes and monasteries, as well as reflecting the pious beliefs of the Tibetan people.

Thangka is a unique form of painting in Tibetan culture. “Thangka” is a transliteration from the Tibetan language, meaning “cloth or silk painting scroll capable of being spread for appreciation.” It originated in the Tobon period (ancient Tibet) around the 7th century. According to legend, the earliest Thangka was a portrait of Goddess Lhamo, which was painted by Songtsan Gambo (c.617-650), king of Tobon. The Bonist culture of Tibet, the inscriptions on precipices and the introduction of Buddhism into Tibet were all factors in expediting the birth and development of Thangka. Boasting distinct national features, strong religious colors and unique artistic style, Thangka has always been regarded by the Tibetans as a treasure.

Thangka has a multitude of qualties, but most Thangka paintings are done on cloth and paper and are called painted Thangka. In addition, there are woven Thangka, which encompass a dozen varieties, including pearl Thangka, color-painted Thangka, embroidered Thangka and brocade Thangka.

Thangka has a multitude of qualties, but most Thangka paintings are done on cloth and paper and are called painted Thangka. In addition, there are woven Thangka, which encompass a dozen varieties, including pearl Thangka, color-painted Thangka, embroidered Thangka and brocade Thangka.

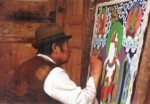

Painting Thangka is a serious matter because it is seen as a practice in adhering to the doctrine of Buddhism. The process of painting is an act of giving to kindness and of practicing virtue and Buddhist doctrine-not the artist’s self-expression of his will. Therefore, the painter must follow a fixed pattern and often has to practice Buddhism for a few days before painting. Some will conduct religious ceremonies and chant Buddhist scripture. Tibetan painters rarely leave their names on the paintings.

It is extremely complicated to paint a Thangka; the act of doing so often lasts several months and even years. It involves many complex procedures, including linearization, colorization, dyeing, contour-sketching with color brushes, tracing designs in gold and inlaying gold.

In painting, the artist uses a fine thread to fasten the cloth onto a wooden frame and applies glue evenly on both sides of the cloth. He coats it with another layer of gypsum powder after it has been air-dried and uses shells and pebbles to polish it until the cloth’s surface is smooth and even, revealing no grains. Then, he uses a carbon stick to sketch the contours of the Buddha and uses a pencil to draw the lines. Pure natural mineral dyestuffs are used, which are bright and durable. It is necessary to use a brush dipped in color to do contour sketching after the application of color and then a gold juice to depict the portrait. Tibetan painters are extremely selective about the quality of the gold powder; it must be pure gold.

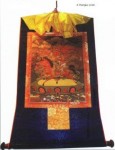

Great attention is also paid to the mounting process once the painting is complete. The four sides of the painting are bordered with multicolored brocade and the top and bottom are fastened with a wooden roller. Many Thangkas have red and yellow borders added and are covered with silk the same size as the painting.

After mounting, Thangkas that incorporate Buddhism are usually sento to a temple or monastery for a consecration ceremony and lamas are invited to chant scriptures and add their fingerprints with gold juice or cinnabar on the back of the painting. This way, a Thangka becomes a holy article.

Aside from religious subject-matter, Thangkas also depict Tibetan medicine, historical events, biographies, customs, legends and fairy tales, involving politics, economy, history, religion, literature, art, and social life. Thus, Thangkas are like an encyclopedia of the Tibetans.

The size of Thangkas varies. The smallest is only the size of a palm, painted on paper, cloth or goat skin; the large ones can be as large as dozens and even hundreds of square meters. When such a huge Thangka is slowly unfolded it can cover a hill slope. A large Thangka titled “A Show of Colored Drawings on Literature and Art of Tibetan Ethnic Group of China” is 618 meters long and took 400 top-level handicraft masters nearly four years to complete.

Developed from the 7th century to the present, Thangka has become a very mature art of painting as well as a religious art. The Buddha and Bodhisattvas painted on Thangkas have replaced sculptures and murals in the monasteries and temples and have become portable idols. As long as the Tibetans who wander in search of water and grass on the vast, desolate plateau roll up a Thangka and hang it in the tent in which they live, they will be able to pray, conduct religious services and receive spiritual sustenance.