The Art of Listening, Old-style Theaters

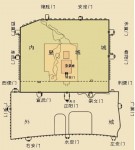

Old Beijing with the Forbidden City at its center. The Outer City in the south is where old-style theaters were concentrated. In the past, people visiting Beijing would invariably go to a theater to see a Peking Opera performance. When we see a show today, we say “watch an opera.” But old Beijingers say “listen to an opera” instead. What counts in Peking Opera is singing, whereas performance is highly stylized. Audiences are wont to listen to singing with eyes shut and hands beating time. When they like a particular line, they would shout “bravo!” These are typical fans.

Old Beijing with the Forbidden City at its center. The Outer City in the south is where old-style theaters were concentrated. In the past, people visiting Beijing would invariably go to a theater to see a Peking Opera performance. When we see a show today, we say “watch an opera.” But old Beijingers say “listen to an opera” instead. What counts in Peking Opera is singing, whereas performance is highly stylized. Audiences are wont to listen to singing with eyes shut and hands beating time. When they like a particular line, they would shout “bravo!” These are typical fans.

Old-style theaters where Peking Opera was performed before the 1950s were called xiyuanzi, which literally means “opera courtyard.” Facilities in a xiyuanzi were rather simple. The stage was square, with three sides extending right into rows of seats for the audience. At an early date in the Qing period (1644-1911), xiyuanzi was called “tea courtyard.” At the time, audiences paid for the tea but not the opera they watched. For customers, their main purpose in coming to the “tea courtyard” was to drink tea, whereas watching an opera was sort of “incidental.” In the Qing period, a show in a xiyuanzi could last as long as 10-12 hours, all in the daytime. Customers also paid for snacks such as sunflower seeds and roasted peanuts. Tea charge was not charged until before the start of the last but one item on the day’s theatrical program. A striking feature of xiyuanzi in old Beijing was “hot towel throw.” Waiters, shouting “here comes the towel,” would throw steaming towels to audiences, with great accuracy. Waiters accepted tips and never haggled over their size. Tianqiao area in Beijing used to be a center of folk culture”

“Tea courtyards” were later called xiyuanzi, or old-style theater. In the period of the Republic of China (1911-1949), they became known as theaters, and the stage was patterned after stages in the West. Xiyuanzi, which was of a traditional architectural style, was smaller than a typical Western theater in capacity, but what audiences heard in a xiyuanzi was original singing of actors and actresses, free of a loudspeaker.

In the middle and latter periods of the 19th century, as Peking Opera gained popularity, the number of xiyuanzi in Be?ing increased, and most of them were located in a flourishing commercial district south of the Qianmen Gate Tower. Viewed from above, the district is situated on the city’s north-south axis. The stage in an old-style theater was not big. Stages were first paved with wooden planks and later covered with carpets. This was to make sure that actors making summersaults would not hurt themselves. At the stage front were usually erected two columns on which were written words in praise of a troupe performing at the time. In the rear of the stage hung an embroidered curtain, which was the private property of the leading actor of the day. The curtain bore patterns of flowers and birds, in a style compatible with the leading actor. Seeing the curtain, audiences knew who was going to play the lead.

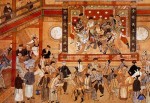

The photo of the mural was taken during the Republic of China period (1911-1949). Photo by courtesy of Mei Lanfang Museum. Below the stage was dirt ground. Later, ground was paved with bricks and still later with cement. In an early period, audiences sat on benches facing one another across oblong wooden tables. This sitting posture facilitated chatting and eating snacks but was not suitable for watching a theatrical performance. It is not until after 1914 that long benches with back support were placed parallel to the stage, enabling audiences to face the stage. On the back of the benches were nailed long- framed planks, on which were placed teacups. At the time, men and women were separated at old-style theaters, with men sitting downstairs and women sitting upstairs. It is not until 1931 that men and women sat together. At the back of the rows of seats was usually placed an oblong table with the sign “The Suppression Seat” on it. When a play started, fully-armed soldiers came to sit behind the table to deal with any possible commotion. On a holiday the theater owner would hand them envelopes stuffed with money to seek their protection.

The photo of the mural was taken during the Republic of China period (1911-1949). Photo by courtesy of Mei Lanfang Museum. Below the stage was dirt ground. Later, ground was paved with bricks and still later with cement. In an early period, audiences sat on benches facing one another across oblong wooden tables. This sitting posture facilitated chatting and eating snacks but was not suitable for watching a theatrical performance. It is not until after 1914 that long benches with back support were placed parallel to the stage, enabling audiences to face the stage. On the back of the benches were nailed long- framed planks, on which were placed teacups. At the time, men and women were separated at old-style theaters, with men sitting downstairs and women sitting upstairs. It is not until 1931 that men and women sat together. At the back of the rows of seats was usually placed an oblong table with the sign “The Suppression Seat” on it. When a play started, fully-armed soldiers came to sit behind the table to deal with any possible commotion. On a holiday the theater owner would hand them envelopes stuffed with money to seek their protection.

During the early stage of xiyuanzi, there were no newspapers, nor were there ads and posters. The method of promotion was to place at the xiyuanzi gate stage properties for the evening’s show. For people who loved Peking Opera, a look at the stage properties was enough for a guess at what the show was for the evening. For example, a block of stone pointed to The Yanyang Building (yan yang lou) and a big spear Battling Down-sliding Chariots (tiao hua che). A heap of weapons of different kinds indicated that the evening’s last play would be Havoc in Heaven (nao tian gong). The weapons were used to subdue the Monkey King, hero of the play. A day’s program was printed on a piece of yellow paper with a wood block and sold for a penny or two. It is not until after the 1920s that programs were printed with lead types.

During the early stage of xiyuanzi, there were no newspapers, nor were there ads and posters. The method of promotion was to place at the xiyuanzi gate stage properties for the evening’s show. For people who loved Peking Opera, a look at the stage properties was enough for a guess at what the show was for the evening. For example, a block of stone pointed to The Yanyang Building (yan yang lou) and a big spear Battling Down-sliding Chariots (tiao hua che). A heap of weapons of different kinds indicated that the evening’s last play would be Havoc in Heaven (nao tian gong). The weapons were used to subdue the Monkey King, hero of the play. A day’s program was printed on a piece of yellow paper with a wood block and sold for a penny or two. It is not until after the 1920s that programs were printed with lead types.

Peking Opera had a close relationship with the Qianmen Gate Tower area in Beijing, which was a cradle of folk culture in the city. In the early years of Peking Opera, the Qianmen Gate Tower area was where the city’s entertainment, catering industry, commerce and people’s cultural activities were concentrated. It is right in this area that Peking Opera grew and thrived. Not only were Peking Opera’sold theaters and the homes of actors and actresses concentrated here, but many Peking Opera fans and people connected with theatrical shows lived in the area, too. In the more than 50 years from the early 20th century to 1957, the Qianmen Gate Tower area was home to some 600 famous artists of Peking Opera, pingju opera, acrobatics and quyi (folk art forms including ballad singing, story telling, comic dialogues, clapper talks and cross talks). These performing artists had learned their art from different masters and each had his unique skill. At the time, Tianqiao south of the Qianmen Gate Tower was a thriving, densely populated downtown area of Beijing. And Tianqiao’s soul was Beijing’s traditional folk culture.

dialogues, clapper talks and cross talks). These performing artists had learned their art from different masters and each had his unique skill. At the time, Tianqiao south of the Qianmen Gate Tower was a thriving, densely populated downtown area of Beijing. And Tianqiao’s soul was Beijing’s traditional folk culture.