The Thousand Faces of the Tang Costume

In terms of cultural and economic development of the feudal society, the Tang Dynasty in China was doubtless a peak in the development of human civilization. The Tang government not only opened up the country to the outside world, allowing foreigners to do business and come to study, but went so far as to allowing them in exams for selection of government officials. It was tolerant, and often appreciative, of religions, art and culture from the outside world. Chang’an, the Tang capital, therefore became the center of exchange among different cultures. What is worth special mention is that women of the Tang Dynasty did not have to abide by the traditional dress code, but were allowed to expose their arms and back when they dressed, or wear dresses absorbing elements from other cultures. They could wear men’s riding garments if they liked, and enjoyed right to choose their own spouse or to divorce him. Materialistic abundance and a relatively relaxed social atmosphere gave Tang Dynasty the unprecedented opportunity to develop culturally, reaching its height in poetry, painting, music and dance. Based on the development in textiles in the Sui Dynasty, and progress made in silk reeling and dyeing techniques, the variety, quality and quantity of textile materials reached unprecedented height, and the variety of dress styles became the trend of the time.

Tang Dynasty in China was doubtless a peak in the development of human civilization. The Tang government not only opened up the country to the outside world, allowing foreigners to do business and come to study, but went so far as to allowing them in exams for selection of government officials. It was tolerant, and often appreciative, of religions, art and culture from the outside world. Chang’an, the Tang capital, therefore became the center of exchange among different cultures. What is worth special mention is that women of the Tang Dynasty did not have to abide by the traditional dress code, but were allowed to expose their arms and back when they dressed, or wear dresses absorbing elements from other cultures. They could wear men’s riding garments if they liked, and enjoyed right to choose their own spouse or to divorce him. Materialistic abundance and a relatively relaxed social atmosphere gave Tang Dynasty the unprecedented opportunity to develop culturally, reaching its height in poetry, painting, music and dance. Based on the development in textiles in the Sui Dynasty, and progress made in silk reeling and dyeing techniques, the variety, quality and quantity of textile materials reached unprecedented height, and the variety of dress styles became the trend of the time.

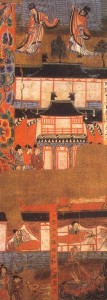

The most outstanding garments in this great period of prosperity were women’s dresses, complimented by elaborate hairstyles, ornaments and face makeup. The Tang women dressed in sets of garments, each set a unique image in itself. People no longer dressed by their whims, but played up the full beauty of their garment based on their social background. Each matching set of garments had its own unique character, as well as a deep cultural grounding. In general, the Tang women’s dresses can be classified into three categories: the hufu, or alien dress that came from the Silk Road, the traditional ruqun or double layered or padded short jacket that w as typical of central China, as well as the full set of male garments that broke the tradition of the Confucian formalities. Let’s first talk about the ruqun, which is made up of the top jacket and long gown and a skirt on the bottom. The Tang women inherited this traditional style and developed it further, opening up the collar as far as exposing the cleavage between the breasts. This was unheard of and unimaginable in the previous dynasties, in which women had to cover their entire body according to the Confucian classics. But the new style was soon embraced by the open-minded aristocratic women of the Tang Dynasty. Zhang Xuan, a woman painter of the Tang Dynasty, and Zhou Fang, another famous painter, were particularly good at portraying opulent women in elaborate dresses. Zhou Fang, in his painting Lady with the Flower in the Hair, portrayed a beauty with a long gown lightly covering the breasts, revealing soft and supple shoulders under a silk cape.

The chart of the make-up order for Tang Dynasty women. A facial make-up of Tang women. (Drawn by Gao Chunming)

The Tang aesthetics was that of suppleness and opulence, like peonies in flowers, men and women with short necks and shoulders, and horses with small head, thick neck and a large backside. In Tang paintings, women tried to show their suppleness by pleating their skirts in accordion form, and raised the waist all the way up to under the armpits, so that the waistline was barrel shaped to show a full and round body contour. Descriptions of the Tang dresses were found in a vast array of poems, both in terms of style and color. A vast array of colors was found in the poems, because there was no official decree on what color was or was not appropriate. Personal preference was all that mattered, be it deep red, apricot yellow, deep violet, ultramarine, sap green or turmeric. Pomegranate red was popular for the longest time. In poems by Li Bai, Du Fu and Bai Juyi, the most outstanding poets of the time, lady in pomegranate skirt was an enduring image of beauty. Song of May in Yanjing had an interesting account of the pomegranatered skirt. It was so popular that in the season when pomegranate blossoms colored the city in red, every household was buying the flower to dye the dresses of their girls. Turmeric skirt was also colored with vegetable dye. The skirt had the beauty of the turmeric color as well as the fragrance that stayed in the skirt. A feather skirt worn by a princess in the mid Tang Dynasty was woven with feathers from a hundred birds. An outstanding piece of work in the history of Chinese costume and textiles, the skirt had varying colors in daytime and at night, under sunlight and under night light, held upright and upside-down. Moreover, images of birds were woven all over the skirt, coming to life in the play of light.

There is more to the woman’s ruqun than the upper and lower garment. The dress had many matching accessories and ornaments to go with it, including a short sleeve shirt called banbi or half-arm, worn outside of the long sleeve jacket, unlike what we do now in summertime. Named a half-arm because the length of the sleeve was somewhere between the vest and the long sleeve, it functioned just like a vest. The Tang women favored the pizi or cape, or as an alternative, a large piece of silk draped over the arms. The difference is that the cape was wide and short, draped over one shoulder of the wearer. The cape is seen on many clay burial figurines unearthed from Tang tombs. There was a story that the Imperial Concubine Yang Yuhuan had her cape blown away onto someone’s hat during a royal banquet. Judging from this story the cape must have been light and thin, although we cannot exclude the possibility that heavier capes made from wool were used in winter to shield the body from the cold wind. The pibo, however, is much longer and narrower. Draped over the shoulder from back to front, it is what we normally call the “ribbon” – a beautiful piece rarely forgotten in classic Chinese paintings. Footwear to go with ruqun includes brocade shoes with tipped-up “phoenix head” toes, and shoes made with flax or cattail stems, all very light and delicate. In addition to images in classic paintings, we are able to see real pieces unearthed in Xinjiang and other places. When wearing the ruqun, the Tang women rarely wore hats. Sometimes they wore decorative flower crowns, but when out, they often covered their faces with a veil. This kind of veil hat became the trend in the early Tang Dynasty, but by mid-Tang Dynasty many no longer bothered to wear it, but chose to show their hair buns when they were out riding. There was a large variety of hairstyles at that time, all competing for opulence and extravagance, including over 30 kinds of tall buns, double buns, and downward buns, most of which named after their shapes. Some of these hairstyles came from ethnic minority groups. A full range of ornamental objects was used on the buns, including gold hairpins, jade ornaments, as well as fresh or silk flowers. This is often seen in Tang paintings, as well as in artifacts unearthed in ancient tombs.

There is more to the woman’s ruqun than the upper and lower garment. The dress had many matching accessories and ornaments to go with it, including a short sleeve shirt called banbi or half-arm, worn outside of the long sleeve jacket, unlike what we do now in summertime. Named a half-arm because the length of the sleeve was somewhere between the vest and the long sleeve, it functioned just like a vest. The Tang women favored the pizi or cape, or as an alternative, a large piece of silk draped over the arms. The difference is that the cape was wide and short, draped over one shoulder of the wearer. The cape is seen on many clay burial figurines unearthed from Tang tombs. There was a story that the Imperial Concubine Yang Yuhuan had her cape blown away onto someone’s hat during a royal banquet. Judging from this story the cape must have been light and thin, although we cannot exclude the possibility that heavier capes made from wool were used in winter to shield the body from the cold wind. The pibo, however, is much longer and narrower. Draped over the shoulder from back to front, it is what we normally call the “ribbon” – a beautiful piece rarely forgotten in classic Chinese paintings. Footwear to go with ruqun includes brocade shoes with tipped-up “phoenix head” toes, and shoes made with flax or cattail stems, all very light and delicate. In addition to images in classic paintings, we are able to see real pieces unearthed in Xinjiang and other places. When wearing the ruqun, the Tang women rarely wore hats. Sometimes they wore decorative flower crowns, but when out, they often covered their faces with a veil. This kind of veil hat became the trend in the early Tang Dynasty, but by mid-Tang Dynasty many no longer bothered to wear it, but chose to show their hair buns when they were out riding. There was a large variety of hairstyles at that time, all competing for opulence and extravagance, including over 30 kinds of tall buns, double buns, and downward buns, most of which named after their shapes. Some of these hairstyles came from ethnic minority groups. A full range of ornamental objects was used on the buns, including gold hairpins, jade ornaments, as well as fresh or silk flowers. This is often seen in Tang paintings, as well as in artifacts unearthed in ancient tombs.

Although facial makeup was not invented by the Tang women, they were quite elaborate and extravagant. They not only powdered their faces, darkened their eyebrows, rouged their cheeks or put on lipsticks. These women also decorated their foreheads with a yellow crescent, which was said to be an imitation of the northwestern ethnic minorities. Eyebrows were painted in different shapes. It was said that the Xuanzong Emperor asked his court painter to record the ten eyebrow styles, which all had different names, such as the “mandarin duck,” the “small peak,” the “drooping pearl,” and the “dark fog.” The commoners had their own trendy brow styles as well. Moreover, decorative designs are put between the eyebrows as a finishing touch, made with feathers, seashells, fish bones, pure gold, or just painted on. At the tip of each eyebrow there is a “red slant.” Lips are painted into the trendiest shapes of the time, complimented by an artificial red dimple about one centimeter from each side of the lips. At the most prosperous time of the Tang Dynasty, these dimples went so far as to reach the two sides of the nose, in shapes of coins, peaches, birds and flowers. We can see this kind of dimples in the Dunhuang Grottos of the Five Dynasties.

quite elaborate and extravagant. They not only powdered their faces, darkened their eyebrows, rouged their cheeks or put on lipsticks. These women also decorated their foreheads with a yellow crescent, which was said to be an imitation of the northwestern ethnic minorities. Eyebrows were painted in different shapes. It was said that the Xuanzong Emperor asked his court painter to record the ten eyebrow styles, which all had different names, such as the “mandarin duck,” the “small peak,” the “drooping pearl,” and the “dark fog.” The commoners had their own trendy brow styles as well. Moreover, decorative designs are put between the eyebrows as a finishing touch, made with feathers, seashells, fish bones, pure gold, or just painted on. At the tip of each eyebrow there is a “red slant.” Lips are painted into the trendiest shapes of the time, complimented by an artificial red dimple about one centimeter from each side of the lips. At the most prosperous time of the Tang Dynasty, these dimples went so far as to reach the two sides of the nose, in shapes of coins, peaches, birds and flowers. We can see this kind of dimples in the Dunhuang Grottos of the Five Dynasties.

These facial makeup styles were not the invention of the Tang Dynasty, but rather had their roots in the previous dynasties. For example, the Huadian or forehead decoration was said to have originated in the Southern Dynasty, when the Shouyang Princess was taking a walk in the palace in early spring and a light breeze brought a plum blossom onto her forehead. The plum blossom for some reason could not be washed off or removed in any way. Fortunately, it looked beautiful on her, and all of a sudden became all the rage among the girls of the commoners. It is therefore called the “Shouyang makeup” or the “plum blossom makeup.” This makeup was popular among the women for a long time in the Tang and Song Dynasties. As for the “red slant,” it was said that Cao Pi, Weiwen Emperor of the Three Kingdoms Period, had a favorite imperial concubine named Xue Yelai. One night when Cao Pi was reading, Xue Yelai came by and accidentally hurt her temple on the crystal screen. When the wound healed, the scar remained, as did the love of the emperor. All girls in court tried to imitate her, painting a red mark on both sides of the face. This kind of makeup was initially called the “morning sun makeup,” as the color was close to the rosy dawn. It was later called the “red slant” Concerning the eyebrows, it was said in a Song Dynasty history book that the Yang Emperor of the Sui Dynasty noticed a girl with painted long eyebrows among thousands of beautiful women in a boat ride in the dragon and phoenix shaped boats.

When finally the Tang women decided there was no space left for painting on the face, they all of a sudden changed their makeup style. According to history book, after the mid-Tang Dynasty, the trend became not wearing power or rouge on the face. The only makeup that remained was the black lipstick. It was called the “weeping makeup” or “tears makeup”. Compared with the gorgeous dress of the ruqun, a full set of men’s riding attire on women had its own unique flavor. The typical men’s wear in the Tang Dynasty included the futou or turban, round collar jacket and gown, belt on the waist and dark leather boots. Women dressed like this look sharp, unrestrained yet elegant. Although in Confucian teachings long ago it was said that men and women should never cross-dress, women in men’s dressed are frequently seen in Tang paintings and in the Dunhuang Grottos. Historical records on Tang garments all told us that in those days, Tang women often wore full sets of men’s clothes including boots, gowns, horsewhips and hats. Aristocrats, commoners, at home, or going out, many women dressed like this in those days. It is not hard to imagine that Tang was a rather open society as far as women are concerned. Such is the extravagance of the Tang garments. Nowadays people call any front closure Chinese jacket the “Tang costume,” as a general term for addressing all traditional Chinese garments. However, the term is used only because people today take pride in those prosperous days. In reality, the modern “Tang costumes”have far less of the luster, extravagance and vitality compared to the real thing. The grandeur of the metropolis where all nations came to admire made the Tang Dynasty nothing short of the kingdom of garments.

When finally the Tang women decided there was no space left for painting on the face, they all of a sudden changed their makeup style. According to history book, after the mid-Tang Dynasty, the trend became not wearing power or rouge on the face. The only makeup that remained was the black lipstick. It was called the “weeping makeup” or “tears makeup”. Compared with the gorgeous dress of the ruqun, a full set of men’s riding attire on women had its own unique flavor. The typical men’s wear in the Tang Dynasty included the futou or turban, round collar jacket and gown, belt on the waist and dark leather boots. Women dressed like this look sharp, unrestrained yet elegant. Although in Confucian teachings long ago it was said that men and women should never cross-dress, women in men’s dressed are frequently seen in Tang paintings and in the Dunhuang Grottos. Historical records on Tang garments all told us that in those days, Tang women often wore full sets of men’s clothes including boots, gowns, horsewhips and hats. Aristocrats, commoners, at home, or going out, many women dressed like this in those days. It is not hard to imagine that Tang was a rather open society as far as women are concerned. Such is the extravagance of the Tang garments. Nowadays people call any front closure Chinese jacket the “Tang costume,” as a general term for addressing all traditional Chinese garments. However, the term is used only because people today take pride in those prosperous days. In reality, the modern “Tang costumes”have far less of the luster, extravagance and vitality compared to the real thing. The grandeur of the metropolis where all nations came to admire made the Tang Dynasty nothing short of the kingdom of garments.